Heavyweight insulin maker Novo Nordisk said Tuesday that it will lower list prices for some of its insulin products by up to 75 percent by the end of the year, following in the footsteps of Eli Lilly, which made a similar announcement at the start of the month. Experts expect the third top insulin maker in the US, Sanofi, will follow suit.

The price cuts come after years of escalating public backlash to the companies' steep price hikes on insulin, which many advocates have described as price gouging. An analysis from 2018 found that insulin list prices were set five- to ten-times higher in the US than in other high-income countries, with average standardized units of insulin going for nearly $100. The cost of producing the products, even the newer insulins, generally falls under $10.

In its announcement Tuesday, Novo Nordisk said that it will cut the prices of several products, including Levemir, Novolin, NovoLog, and NovoLog Mix 70/30. With the 75 percent cut, a 10mL vial of NovoLog will drop from $289.36 to $72.34. A NovoLog Mix 70/30 FlexPen will drop from $558.83 to $139.71.

Amid public outrage over the prices, lawmakers have also been working on ways to force prices down. The companies' voluntary price cuts closely track a federal price cap that went into effect this year via the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The law limits out-of-pocket insulin costs to $35 per month for Medicare Part D beneficiaries. When Eli Lilly slashed its prices earlier this month, it also announced programs that cap monthly insulin costs to $35 for people with commercial insurance as well as the uninsured. Novo Nordisk did not offer such a cap in its announcement today, though it noted a hodgepodge of deals and programs.

But, while the price cuts may seem linked to last year's Inflation Reduction Act, health policy experts and lawmakers note that a slightly older law may be the real impetus behind the dramatic cuts—the American Rescue Plan of 2021. The law contained a number of provisions to improve healthcare access and affordability, including one that eliminates a cap on rebates that drug companies are required to pay Medicaid. If the cap was lifted with insulin list prices set as they are now, insulin makers might have had to pay Medicaid programs more than the price of their insulin products every time a Medicaid program had to cover one, likely totaling tens of millions of dollars in payments to Medicaid. But, with the lower list prices, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk will dodge those extra payments. The rebate cap is set to lift January 1, 2024—which is also when the companies' price cuts will fully kick in.

The rebate program cap is a little complicated, so here's a breakdown of how it works. It all stems from the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), passed by Congress under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. The straightforward goal of the MDRP was to make sure that Medicaid paid the lowest or best possible price for prescription drugs. As such, drug makers who want their drugs covered by Medicaid have to enter into a rebate agreement, under which Medicaid agrees to cover and purchase their products as long as the drug makers pay them back a rebate to keep costs as low as possible. The cost of the rebate is based on a set of formulas that consider things like the type of drug—brand or generic—and market prices.

Cold calculations

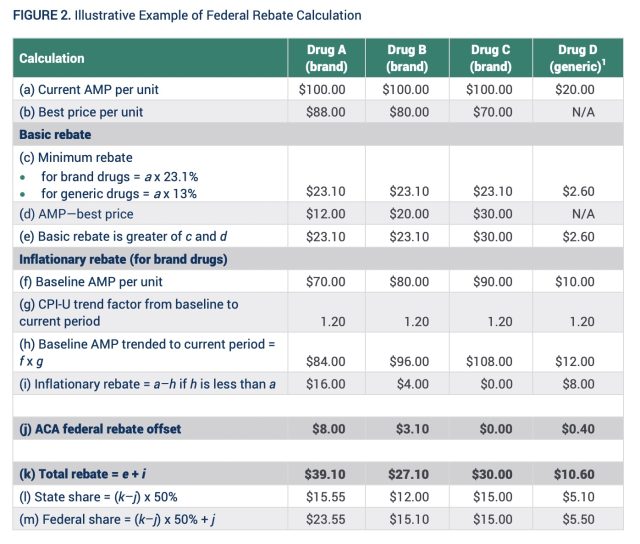

For a brand drug, the basic rebate that a drug maker will pay Medicaid is 23.1 percent of the average manufacturer price or the difference between the average price and the best (lowest) price, whichever is higher. In an example laid out by the federal Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), if a brand drug has an average manufacturer price of $100, and the best market price is $88, the drug maker will pay the standard percentage, equaling $23.10, for the basic rebate. But, if the average price is $100 and the best price is $70, the basic rebate would be $30.

Under current law, the rebate was capped at the current average price. That is, drug makers wouldn't be required to pay a rebate that exceeded 100 percent of their drug's average manufacturer price. But, with drug prices skyrocketing well past inflation, that meant a lot of money was left on the table. A federal analysis of drug rebates in 2012, for instance, found that 54 percent of brand drug rebates were from the inflationary component. And in 2019, the rebate cap allowed drug makers to avoid paying a whopping $3 billion in rebates, according to a Congressional budget office estimate.

Based on the current prices for insulin, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk would easily end up paying Medicaid rebates that exceed the average manufacturer price of their drugs, thanks to the companies' steep price increases that blew past rates of inflation over the years. For instance, Sean Dickson, a drug-pricing expert at the nonprofit West Health Policy Center, told Politico that Medicaid would have ended up generating an estimated $150 in revenue for every vial of Humalog it covered, amounting to about $140 million in annual Medicaid payments from Eli Lilly.

With the list prices now set to fall, Medicaid may end up paying more than it did before for insulin products, though it's unclear by how much.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.