On May 7, health officials in the UK reported a case of monkeypox in a person who had recently traveled to Nigeria. The case was very rare but not necessarily alarming; a small number of travel-related cases of monkeypox pop up now and then. The UK logged seven such cases between 2018 and 2021. But this year, the cases kept coming.

By May 16, the UK had reported six additional cases, mostly unconnected, and all unrelated to travel, suggesting domestic transmission. On May 18, Portugal reported five confirmed cases and more than 20 suspected ones. The same day, health officials in Massachusetts reported the first US case. Spain, meanwhile, issued an outbreak alert after 23 people showed signs of the unusual infection. Cases in Italy and Sweden followed.

In the past, monkeypox transmission largely fizzled out on its own. Experts did not consider the virus to be easily transmissible. Still, the cases kept coming. By May 26, the multinational outbreak had exceeded 300 cases in over 20 countries. At the time, the US had only nine cases confirmed, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that it presumed domestic community transmission was already underway. In early June, the global tally exceeded 1,300 from 31 countries, including 45 cases in the US.

As June turned into July, health experts around the world scrambled to address the mushrooming outbreak. On July 23, with global cases at over 16,000 from more than 70 countries, the World Health Organization declared the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). It's the agency's highest level of alert—and a level many health experts said should have been reached in June.

Soon after the PHEIC declaration, the US took the global lead for the highest monkeypox case tally. And on August 4, with over 6,600 cases in 48 states, the US government declared the outbreak a public health emergency.

As of August 9, just over four months since the first case was reported in the UK, there are more than 30,000 monkeypox cases reported from at least 88 countries, including at least 11 deaths. The US case count is now over 8,900.

Below is a practical reference guide for all the important information on this global and national health emergency. The guide will be updated periodically as new information becomes available.

What is monkeypox?

The virus

Monkeypox is a virus—an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus, to be specific. It belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family, which also includes the variola virus, the cause of smallpox. The monkeypox virus causes a disease similar to that of its eradicated relative, but the disease (also called monkeypox) is generally less severe.

Animal hosts

The name "monkeypox" is a bit of a misnomer. The name came about because the virus was first discovered among monkeys at a research facility in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1958. The virus caused two non-fatal outbreaks that year at the facility after shipments of Asian monkeys arrived from Singapore.

However, monkeys are not the sole or even the primary host for the virus—the research animals just happened to be where the virus was first spotted. The virus can infect a wide range of non-human primates and rodents, including rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, and prairie dogs. It's still unclear exactly which animals act as its reservoir—its natural host—but experts think the reservoir is most likely rodents, not monkeys.

Where it’s usually found

The monkeypox virus is endemic to countries in Western and Central Africa, typically in tropical rainforest areas. The WHO considers monkeypox-endemic countries to include Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Ghana (identified in animals only), Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, and Sierra Leone.

The first human case of monkeypox was identified in a 9-month-old baby boy in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970.

Clades

There are two clades of monkeypox virus, which are currently named based on their geography: the West African clade and the Congo Basin clade. Of the two, the West African clade is considered milder, with a case fatality rate of 3.6 percent compared with the Congo Basin clade's 10.6 percent rate, according to the WHO. For the clades' geographical distributions, Cameroon acts as the dividing line. It is the only country in which both clades have been identified.

The milder West African clade is the one circulating in the current outbreak.

Naming controversies

The misnomer virus and disease names and the geographically linked clade names have all drawn criticism during the current outbreak. Health experts now regard them as misleading, stigmatizing, and having racist overtones. As such, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, which has authority over naming viruses, is considering revising the name of the virus. The WHO, which has authority over the disease name, is considering changing the name. But such changes could take a long time and will require buy-in from the scientific community.

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

People infected with the virus usually develop symptoms between six to 13 days after exposure, but the incubation can range from five to 21 days.

Historically, monkeypox cases begin with a flu-like illness that lasts between one and three days with symptoms that can include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Intense headache

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Back pain

- Muscle aches

- Fatigue/loss of energy

- Respiratory symptoms: sore throat, nasal congestion, and cough

- In some instances, gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting

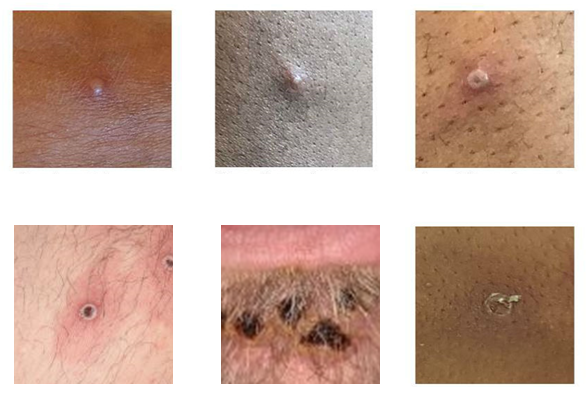

After this stage of this illness, the characteristic rash usually develops. Historically, lesions have formed all over the body and concentrate on the face and extremities, particularly the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. The lesions go through four stages, beginning as flat, discolored spots (macules) that become raised and painful (papules). They then fill with clear liquid (vesicles) and then with pus (pustules). Finally, the pustules crust over, forming a scab that eventually falls off.

This rash can last two to four weeks in all. A person is considered no longer infectious only after all the lesions' scabs have fallen off, and a fresh layer of skin has formed in their place.

Complications of monkeypox can include secondary infections, bronchopneumonia, sepsis, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), and an eye infection, which can lead to vision loss. Those most at risk of severe outcomes include those with compromised immune systems, children, and pregnant people.

As mentioned above, the historic fatality rate among infections with the milder West African clade is estimated to be 3.6 percent, and the Congo Basin clade's fatality rate has been 10.6 percent.

How the disease is presenting in this outbreak

In this outbreak, many cases have not fit the mold of previous monkeypox diseases. For instance, many cases have been linked to sexual activity. As such, many patients have reported lesions occurring in the mouth and genital and anal areas. Sometimes the rashes are not spreading over the whole body, and there may only be a few lesions or even a single one.

Moreover, some infected people are not experiencing a flu-like illness before their rash. Some are experiencing it after developing a rash or not at all. For these reasons, many cases have initially been mistaken for common sexually transmitted infections, such as herpes, syphilis, and gonorrhea. Many have described the lesions as excruciating, and some people have been hospitalized for pain management. Lastly, many have reported rectal symptoms, including rectal pain, rectal swelling, and passing stools with pus or blood.

"We're seeing new manifestations of illness," Rosamund Lewis, WHO's technical lead for monkeypox, said in a recent question-and-answer event. Those new manifestations include conditions "that can be extremely painful and need medical care, such as secondary infections or such as inflammation or swelling of the rectum," she said.

Though deaths have been rare in the current outbreak, some have occurred in people with compromised immune systems. Others have occurred in otherwise healthy people after they developed encephalitis, a known complication of monkeypox.

How does monkeypox spread?

Generally, the monkeypox virus transmits through direct touch, close-range respiratory droplets over a prolonged time, and through contact with highly contaminated materials, such as bed linens and clothes that have touched people's skin lesions. Overall, the lesions are considered the primary concern, as they are teeming with virions.

The virus can also transmit from a pregnant person to a fetus. Infections during pregnancy can lead to complications, congenital defects, and stillbirths.

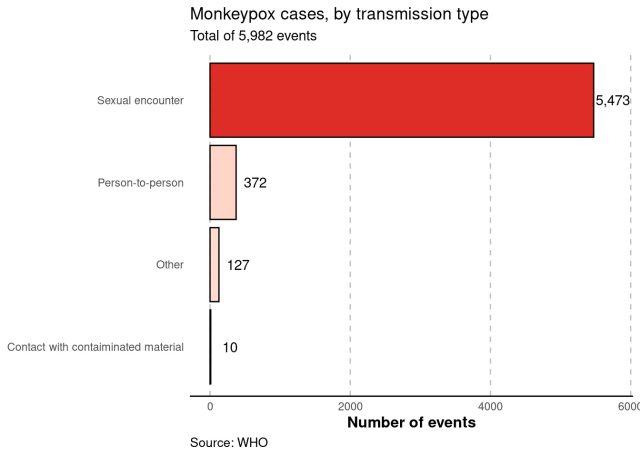

In the current outbreak, the virus is primarily spreading through sexual networks of men who have sex with men (MSM) during sexual activity.

Past spread

In the decades since monkeypox was discovered, experts have considered it to be a virus that is not easily spread. Prior to the current outbreak, human cases usually only occurred when the virus would spill over from an animal host in an endemic region. People most at risk were hunters or people who handled bushmeat. Being bitten or scratched by an infected animal can also transmit the virus.

In these past spillover events, the virus didn't spread far. The WHO notes that the longest documented chains of transmission before the current outbreak included just six to nine successive jumps from person to person before transmission hit a dead end. Those transmission chains were usually limited to health care workers and household members—those who would have close, intimate, prolonged contact with an infected person.

Spread in the current outbreak

In the current outbreak, the virus is clearly spreading in longer chains. And so far, it's unclear why. Experts suspect it could be due to the end of smallpox vaccination, which would have offered cross-protection; an evolution of the virus that allowed it to spread more easily; an exploitation of a new route of transmission—i.e., through sexual networks during sexual activity; or some combination of those factors.

Even so, monkeypox hasn't wholly changed during this outbreak. It's still not an easily transmissible virus. The vast majority of cases are occurring through sexual contact. Thus, as before, transmission is occurring through close, often intimate, prolonged contact—skin-to-skin contact and close face-to-face interactions over an extended period.

The CDC has an explicit description of what that means in this outbreak: "oral, anal, and vaginal sex or touching the genitals (penis, testicles, labia, and vagina) or anus (butthole) of a person with monkeypox." Hugging, massaging, kissing, and face-to-face contact are also transmission risks, as is "touching fabrics and objects during sex that were used by a person with monkeypox and that have not been disinfected, such as bedding, towels, fetish gear, and sex toys," the CDC says.

"What we're talking about here is close contact," Capt. Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the CDC's Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, said in a press briefing back in May. "It's not a situation where if you're passing someone in the grocery store, they're going to be at risk for monkeypox."

The potential for transmission through respiratory droplets has raised alarm and misinformation online. The route is thought to be associated with having lesions in the mouth or throat. But discussion of "respiratory droplets" has raised unpleasant memories of the early days of the pandemic, with some suggesting that monkeypox is similar to the respiratory pathogen SARS-CoV-2. To be clear, monkeypox is not like SARS-CoV-2. They are very different viruses.

Despite the semantics of "airborne" transmission, the monkeypox virus does not linger in the air, travel long distances, or transmit via air over short periods of time. In this outbreak so far, health officials are not documenting cases of people becoming infected by simply sharing airspace with someone.

This squares with what's been seen before. Over the years, a handful of travel-related cases have spurred health officials in the US and the UK to closely monitor airline passengers who were near an infected person. No cases have been identified this way. In the UK, for instance, seven travel-related cases were identified between 2018 and 2021. Of those cases, four were directly imported, two were household contacts, and one was a health care worker.

For now, the current outbreak is spreading primarily through the sexual networks of men who have sex with men (MSM), with transmission occurring during sexual encounters. The vast majority of people infected are men who identify as MSM.

Transmission unknowns

While sex appears to be the main route of transmission in this outbreak, monkeypox is not considered a traditional sexually transmitted infection. Still, it's largely acting like one and is often masquerading as common STIs. Whether monkeypox is spreading through semen, vaginal fluids, feces, or urine is still being investigated.

Another big transmission unknown is whether the virus is transmitting from people with little to no symptoms (asymptomatic spread). In the past, lesions brimming with virions were considered the main risk for transmission. Whether the virus can transmit before people develop or are aware of lesions is still unclear.

Who is at risk?

Though anyone can become infected with monkeypox, for now, those most at risk are MSM. Health experts have called for prevention measures and public health response efforts to focus on these communities.

"This transmission pattern represents both an opportunity to implement targeted public health interventions and a challenge because in some countries, the communities affected face life-threatening discrimination," WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said prior to declaring the outbreak a PHEIC.

The spread among MSM has caused consternation among public health experts. Some have openly fretted about the potential to increase the stigma of MSM by highlighting the true transmission pattern in this outbreak. This has, in some instances, generalized the risk, leaving people at low risk to think they are at high risk—e.g., suggesting that the virus is "airborne." On the other side, though, others have become frustrated that the fear of stigma itself has become a hurdle to the response, preventing health officials from firmly adopting the necessary targeted approaches.

In recent weeks, officials have shifted and honed their messaging. The US CDC has a detailed guide on how MSM members can have safer sex. And last week, WHO Director-General Tedros explicitly advised men who have sex with men to lower their risk by "reducing your number of sexual partners, reconsidering sex with new partners, and exchanging contact details with any new partners to enable follow-up if needed."

Though MSM are at the highest risk right now, everyone should take monkeypox seriously, health experts say. The longer it is able to spread, the more it will spread into new networks of people and potentially become entrenched in countries where the virus is not endemic. Some health experts have noted the potential for the virus to even spill back into animal populations in new countries, thus creating new animal reservoirs that could present a constant risk of transmission moving forward. The risk of this happening is considered very low, however. During a past outbreak in the US involving prairie dogs, for instance, no spread to other animals was noted. (There's more on that below.)

How to protect yourself

For members of the MSM community, the CDC has a detailed guide on safer sex to prevent continued spread in that community. Some health experts, like the WHO Director-General, have suggested that MSM limit the number of sexual partners and avoid anonymous encounters.

For those at risk, there are also two vaccine options, which are discussed in the next section.

In terms of general mitigation efforts, health officials recommend people avoid skin-to-skin contact with anyone who has a monkeypox-like rash. Do not touch such a rash or have close contact—cuddling, hugging, having sex—with someone who has monkeypox. Additionally, avoid contact with materials that an infected person has had a lot of contact with, such as eating utensils, bedding, towels, and clothes. Last, practice good hand hygiene, wash your hands frequently, and use alcohol-based hand sanitizers when out and about.

Monkeypox vaccines and treatments

Vaccines

Two vaccines are used to prevent monkeypox. One is an old-school smallpox vaccine called ACAM2000. This is a single-dose vaccine of a live replicating virus. It takes four weeks after the shot for a person to develop maximum immune protection. But given the replicating virus, it carries serious risks, including a risk of death in one to two cases out of a million doses administered. It is not recommended for people with compromised immune systems or other underlying conditions. As such, it is not the preferred vaccine in this outbreak.

The other, preferred option is the two-dose Jynneos vaccine, which is a live non-replicating virus vaccine that is specifically authorized by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent monkeypox in addition to smallpox. The two doses are administered 28 days apart, and it takes 14 days after the second shot for the vaccine to offer maximum protection.

The vaccine can also be used quickly after an exposure, though the post-exposure efficacy is also unknown. The CDC recommends that post-exposure vaccination occur within four days. After that point, the vaccine may only reduce symptoms, not prevent disease, the CDC warns.

Efficacy

Generally, the efficacy of these vaccines against monkeypox is not clear. Most of the data on the vaccines is based on smallpox work, animal studies, and observational data, not large, rigorous clinical trials. The CDC notes that some data from an observational study in Zaire in the 1980s suggested that prior smallpox vaccination was 85 percent effective at preventing monkeypox. But that study was not looking at people vaccinated with the Jynneos vaccine.

Equity

A bigger problem in this outbreak than the unknown efficacy, however, has been the limited supply of vaccines. Most importantly, vaccine doses are not available in countries in which the monkeypox virus is endemic in animal populations, presenting a stark inequity that has drawn biting criticism from members of the public health community. High-income countries do have access to vaccine supplies, but there is not enough to meet demand.

Dose-sparing

On Tuesday, August 9, the Food and Drug Administration announced that it was authorizing a new way to administer the limited supply of Jynneos vaccines to stretch out the doses for people ages 18 and up. Instead of administering the vaccine subcutaneously (into the tissue under the skin), one-fifth of a dose can be injected into the top layer of skin, causing a bubble. This intradermal injection could maximize immune responses while increasing supply up to five-fold.

“In recent weeks, the monkeypox virus has continued to spread at a rate that has made it clear our current vaccine supply will not meet the current demand,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said in a statement Tuesday. “The FDA quickly explored other scientifically appropriate options to facilitate access to the vaccine for all impacted individuals. By increasing the number of available doses, more individuals who want to be vaccinated against monkeypox will now have the opportunity to do so.”

So far in the outbreak, the US has only gotten 1.1 million doses in hand, which is not enough to vaccinate those at high risk, including certain members of the MSM community, contacts of infected people, and health care workers. In a press briefing on August 9, Dawn O’Connell, assistant secretary for Preparedness and Response for the Department of Health and Human Services, said that of the 441,000 doses yet to be administered, the new method would increase supply to up to 2.2 million doses.

Outside experts applauded the dose-sparing effort, but the efficacy of this strategy is not known, and it may mean that people who are vaccinated now will need more shots in the future. Also, it's unclear how quickly and smoothly the new administration method will roll out into vaccination clinics.

Treatments

For those who become sick with monkeypox, there are a number of treatments available. Though many people will have self-limiting infections that don't require specific treatments, people with severe infections or complications, those who have high-risk factors, children, and pregnant people may be candidates for specialized treatments.

These include:

- The antiviral Tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX, ST-246)

- The antiviral Cidofovir (also known as Vistide)

- The antiviral Brincidofovir (also known as CMX001 or Tembexa)

- Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV), which has been used to treat complications from smallpox vaccination

For all of these treatments, there is no efficacy data against monkeypox specifically. And based on media reports, doctors have had trouble accessing some medications, most notably TPOXX.

What we know about past outbreaks

As noted above, the current outbreak is unusual in its size, its route of transmission (MSM sexual networks), and the way the disease is presenting. But it's not the only outbreak since the virus was discovered in Danish laboratory monkeys in 1958.

In 1964, epidemiologists documented an outbreak at Rotterdam Zoo in the Netherlands that began with the arrival of infected anteaters. The virus subsequently spread to orangutans, gorillas, monkeys, chimpanzees, a gibbon, and a marmoset, many of whom died.

The first outbreak of human cases outside of Africa occurred in the US in 2003. In this outbreak, infected rodents imported from Ghana were housed with pet prairie dogs that contracted the virus and then transmitted it to people. In all, health officials tallied 47 confirmed or suspected monkeypox cases in people from six states: Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin. All of the infected people had direct contact with an infected prairie dog. There was no person-to-person transmission documented. Also, there was no evidence of other animals becoming infected.

In 2017, after decades without any monkeypox cases, Nigeria experienced an outbreak that is still ongoing. In the intervening years, a handful of travel-related monkeypox cases have spread from Nigeria to the US, UK, Singapore, and Israel.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.