Early humans suffered frequent head injuries but often lived long enough for those injuries to heal. That's the result of a study that analyzed twenty 350,000-year-old skulls from a cave in Spain. The study also found that recovery wasn't inevitable—several of the individuals in the cave apparently died from violent blows to the head.

Welcome to the Pit of Bones

About 350,000 years ago, deep in a cave network in what is now northern Spain, the remains of at least 29 people somehow ended up at the bottom of a 13-meter-deep shaft. Paleoanthropologists have unearthed thousands of broken pieces of bone, which add up to the partial skeletons of at least 29 members of a hominin species called Homo heidelbergensis, which may have been a common ancestor of our species and Neanderthals.

The pit, called Sima de los Huesos, contains a mix of ages and genders. Paleoanthropologists are still debating whether the pit was a burial site or just a place where bones washed in with floodwaters.

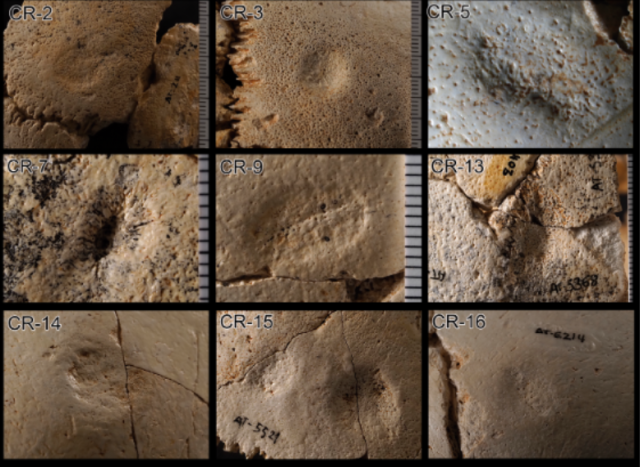

Paleoanthropologists have managed to reconstruct the partial skulls of at least 20 of those long-dead hominins, and most of them appear to have suffered (and survived!) bone-breaking blows to the head. Seventeen out of 20 of the skulls from Sima de los Huesos showed signs of a type of injury called a depressed skull fracture. Evidence of injury isn't terribly surprising in a pit full of skeletons—they must have died somehow, after all. But in this case, the vast majority of the skull fractures were old wounds that had healed long before the individuals died.

When a blunt object—something like a rock or a baseball bat—hits a human skull, it can push a small section of bone inward if the force of the impact is focused in a relatively small area. In the worst cases, the broken plate of bone can put pressure on the brain, or the fracture can leave the brain exposed to bacteria from outside. If neither of those things happens, though, depressed skull fractures usually heal on their own. And that's exactly what happened to most of the early humans who ended up in Sima de los Huesos.

When anthropologist Nohemi Sala of Spain's National Center for Research on Human Evolution and her colleagues examined the skull fragments with a microscope and a CT scanner, they noticed that 17 out of the 20 partial skulls each had at least one small, round dent in its surface. The dents were small and shallow—less than 2 centimeters wide. As the fractures healed, bone remodeled itself over the edges of the fractures, rounding off the sharp edges of broken bone. In other words, these early humans had clearly survived minor head injuries.

A few of the skulls bore the marks of at least 10 healed fractures, suggesting that their former inhabitants were either very violent or very clumsy (or possibly both).

Millions of years’ worth of head trauma

What was happening in Pleistocene Spain to give early humans so many cracked noggins? Nothing that wasn't happening everywhere else, according to Sala and her colleagues.

"This type of nonfatal lesion is relatively common in the Paleolithic fossil record," they wrote. Healed fractures like the ones at Sima de los Huesos have shown up on the skulls of early members of our genus like Homo erectus as well as in Neanderthals and members of our own species. But the burial pit at Sima de los Huesos is rare because it gives us a chance to look at a whole group of hominins rather than just a few isolated individuals. That means paleoanthropologists like Sala and her colleagues can get an idea of how common these injuries were.

It turns out that small skull fractures were common 350,000 years ago and seem to have been a fact of life for nearly everyone. Even the youngest members of the group at Sima de los Huesos had some already-healed fractures, which suggests that everyone had a rough-and-tumble lifestyle from a young age. Male and female skeletons at Sima de los Huesos had about equal numbers of healed fractures, which suggests that men and women faced the same hazards with about the same frequency.

It's hard to say exactly what those hazards were, although we can certainly make some reasonable guesses: fights with other early humans, falls onto hard rocks, or close encounters with wildlife.

Most of the healed fractures were in vulnerable parts of the skull: the areas where only scalp, not muscle, covers the bone. Otherwise, the injuries were scattered around the skulls without any clear pattern to suggest what might have happened. Anthropologists often recognize battle injuries based on their location; if you're holding a club in your right hand and swinging it at another person, for instance, your blow is most likely to land on their left side. But if you're just throwing rocks at the other person, the impacts may look more random.

"We do not rule out that antemortem injuries could have been caused by the impact of projectiles such as rocks, resulting in a random patterns of cranial zones and affected individuals," wrote Sala and her colleagues.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.