Global emissions have continued to burn through the carbon budget, meaning each year brings us closer to having put enough CO2 in the atmosphere that we'll be committed to over 2°C of warming. That makes developing carbon-capture technology essential, both to bring atmospheric levels down after we overshoot and to offset emissions from any industries we struggle to decarbonize.

But so far, little progress has been made toward carbon capture beyond a limited number of demonstration projects. That situation is beginning to change, though, as some commercial ventures start to either find uses for the carbon dioxide or offer removal as a service for companies with internal emissions goals. And the Biden administration recently announced its intention to fund several large capture facilities.

But I recently visited a very different carbon-capture facility, one that's small enough to occupy the equivalent of a handful of parking spaces in the basement of a New York City apartment tower. Thanks to a local law, it's likely to be the first of many. CarbonQuest, the company that installed it, already has commitments from several more buildings, and New York City's law is structured so that the inducement to install similar systems will grow over time.

Carbon city

Because of its vast number of large buildings, New York City has a dizzying variety of fossil fuel-burning hardware tucked away in basements or hidden behind facades. All of the major buildings need significant hardware to provide heat and hot water, and many use co-gen facilities that generate on-site electricity and use the waste heat for these purposes. These co-gen plants can be quite large if they service one of the city's college campuses or major hospitals. There are also steam systems that boil water at a central facility and distribute it through pipes to many buildings.

So while dense urban housing has lower per-capita emissions, individual sources in New York remain considerable and difficult to decarbonize quickly. While the long-term goal would be to switch everything to electric so emissions will go down with grid improvements, it will take many decades for some of this equipment to reach its end of life. And those are decades that New York City's climate goals will not allow.

As a result, the city passed Local Law 97, which sets emissions-based fines starting next year and ramping up over time. The fines are agnostic about how emissions were reduced, however, allowing for the continued use of recent hardware as long as enough of its carbon is kept from reaching the atmosphere. CarbonQuest's business is based on performing that service.

"While we're waiting on this journey for 100 percent renewables, the conversion of electrification, we can take buildings and make a significant impact in their carbon footprint right away," Shane Johnson, the company's CEO, told Ars.

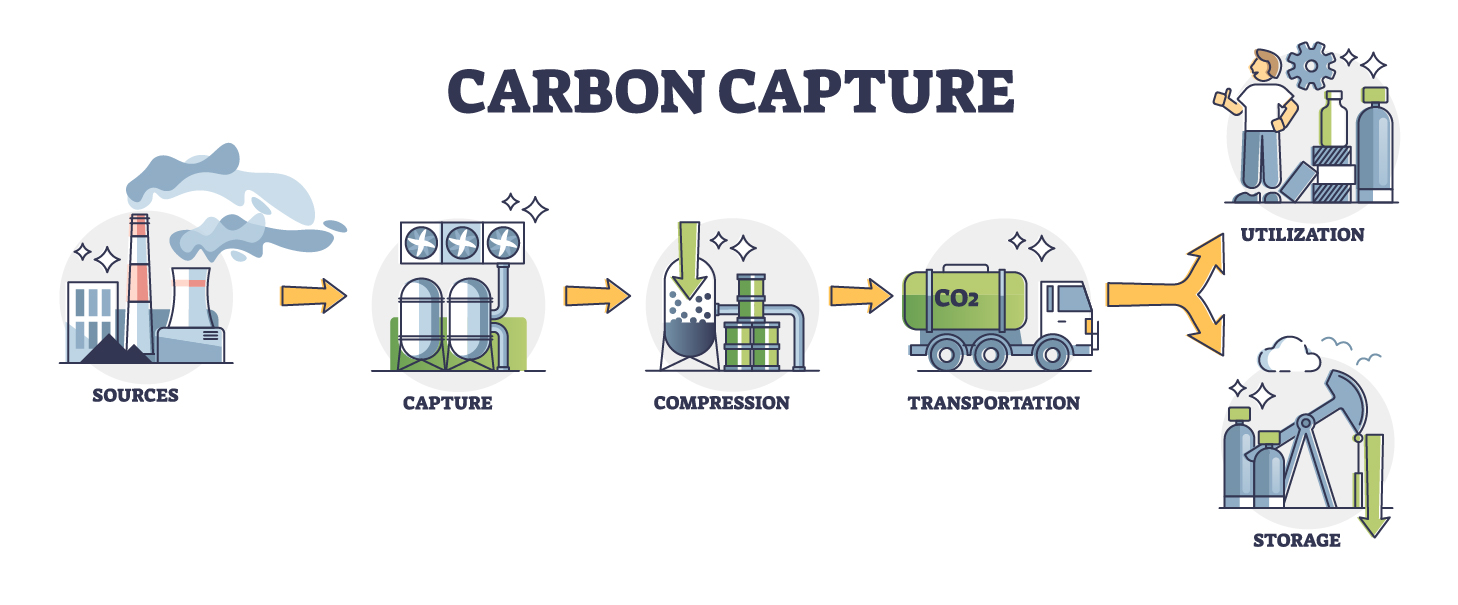

The CarbonQuest's system is designed to work with any hardware that burns natural gas, which can include boilers and combined heat and power systems. It diverts exhaust gases from these systems to a cooler and dehumidifier that pulls out the water. The remaining gas is then pressurized and exposed to a solid material that selectively retains the CO2. Once the remaining gases (mostly nitrogen and oxygen) are removed, the carbon dioxide comes back out. It's then re-pressurized and stored as a liquid until a truck removes it.

-

One of the two gas-fired boilers in the basement of a residential building where CarbonQuest has installed its hardware.John Timmer

One of the two gas-fired boilers in the basement of a residential building where CarbonQuest has installed its hardware.John Timmer -

A diverter sends a portion of the exhaust gasses from the flue into the carbon capture system.John Timmer

A diverter sends a portion of the exhaust gasses from the flue into the carbon capture system.John Timmer -

Almost all of the system, like this compressor, is composed of off-the-shelf hardware from other suppliers.John Timmer

Almost all of the system, like this compressor, is composed of off-the-shelf hardware from other suppliers.John Timmer -

The first step is to remove water vapor from the exhaust gasses.John Timmer

The first step is to remove water vapor from the exhaust gasses.John Timmer -

As a first-of-its-kind installation, CarbonQuest has helpfully labeled many of the components.John Timmer

As a first-of-its-kind installation, CarbonQuest has helpfully labeled many of the components.John Timmer -

The tank on the right is one of a half-dozen in which carbon dioxide is separated from other gasses by a compression/decompression cycle.John Timmer

The tank on the right is one of a half-dozen in which carbon dioxide is separated from other gasses by a compression/decompression cycle.John Timmer -

The end product, ready for pickup.John Timmer

The end product, ready for pickup.John Timmer -

The system has a modular design, defined by pallets outlined in blue metal here. Once in place, pipes connect the hardware on different palettes.

The system has a modular design, defined by pallets outlined in blue metal here. Once in place, pipes connect the hardware on different palettes. -

Tying it all together is a set of monitoring hardware that ensures the system is operating properly and flags when enough carbon dioxide is present to merit a pickup.John Timmer

Tying it all together is a set of monitoring hardware that ensures the system is operating properly and flags when enough carbon dioxide is present to merit a pickup.John Timmer -

This is the only public-facing part of the entire system. A truck can retrieve the liquid carbon dioxide by connecting to a valve in that box.John Timmer

This is the only public-facing part of the entire system. A truck can retrieve the liquid carbon dioxide by connecting to a valve in that box.John Timmer

The process is powered by electricity and doesn't require any consumable materials. "These are smaller plants; they need to operate lights out 24/7, low maintenance, can't have toxic chemicals," Johnson said. "You know, they can't have a guy in a white suit."

The system is modular, allowing it to be constructed from a series of pallets that can fit in a typical freight elevator. This also allows the system to be scaled up to handle higher-volume facilities.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.