For objective careers advice, talk to those who left science as well as those who stayed.

A major flaw in much scientific and academic career advice is survivorship bias. This is a common logical error, involving drawing conclusions based on those who have ‘survived’ a process — and are thus more visible than those who did not. In the case of science careers advice, the bias arises because those who manage to stick to their chosen career path are there to advise the next generation of researchers on how to stay in their field.

As two postdoctoral researchers in ecology (D.H.B., D.R.) and a lecturer in learning and teaching (E.K.), we have seen many examples of worthy but ‘unsuccessful’ colleagues who left their research field against their wishes. On the flipside, the positions we hold in our respective fields are, to some extent, the result of many chance events that we experienced.

Some of our success came from hard work, grit and good judgement. But much of it came from decisions, luck and circumstances that never make it into careers advice. For example, job opportunities for D.R. and her friends have come about through having drinks with senior scientists, and D.R. was invited to publish her first book Does It Fart? thanks to a completely unplanned Twitter hashtag. Chance or serendipitous experiences such as these are impossible to replicate, yet are key to many people’s ability to stay in their chosen career.

Conversely, E.K. had to leave her original field, English literature, because she could not afford to stay in the insecure, low-paid teaching roles that were available. It is therefore important to know not only why some people ‘succeeded’, but also what pushed many more away. Assuming that all aspiring scientists and academics enjoy similar circumstances to those of their colleagues who have ‘survived’ can only damage the prospects of the next generation, and will lead to professions with much less diverse staff than could have been the case.

Over the years, numerous senior researchers have assumed that we would be able to go without pay for an extended period during our research, even while living in one of the world’s most expensive cities. Sometimes we’ve had to argue our case and explain why we couldn’t afford to do so; sometimes we’ve simply had to find other jobs. Anyone who is able to work without pay is not only financially secure but is also unlikely to have other demands such as caring responsibilities — and those who think unpaid work is straightforward are likely to share these circumstances.

For these reasons, survivorship bias in career advice becomes self-perpetuating. Those who survived and thrived because of privilege assume that those hoping to follow in their footsteps are in similar financial and social situations; conversely, those who lack that privilege are less likely to make it to a position from which they can give less biased advice.

As the coronavirus pandemic has blurred the boundaries between ‘work’ and ‘life’, the issue of balance has become even more prominent. The closest many senior researchers come to fostering work–life balance is in offering the common advice to ‘take a break’: perhaps between contracts, over holiday periods, or even by simply not working on weekends. Survivorship bias plays out here as well, because this advice assumes that recipients can afford to take time off despite the pressure to publish or to keep one’s head above water financially. D.R. took a six-month break between handing in her PhD and beginning her postdoc, but this was feasible only because of having savings, thanks to publishing that book about farts — a privileged position that most PhD students cannot easily replicate.

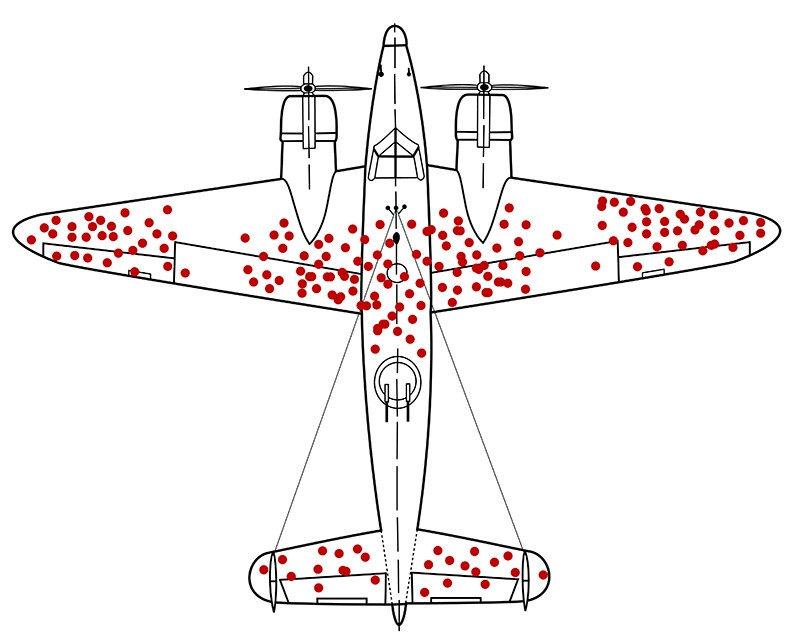

Survivorship bias: during the Second World War, the bullet holes on aircraft that returned marked out the areas that were not crucial to the planes’ integrity.Credit: Martin Grandjean (vector), McGeddon (picture), Cameron Moll (concept) (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Although survivorship bias makes intuitive sense to most academics, its influence in careers advice is rarely considered. Studies that look at career outcomes of current scientists might even conclude that career setbacks are beneficial, without acknowledging that those setbacks lead many others to leave their field altogether1. Some researchers will encounter barriers and setbacks beyond anything we have experienced, for example active discrimination, harassment or severe financial distress, and leave their fields as a result. It is important to understand what the advice that our communities pass on is rooted in, and that none of us can be truly representative of all aspiring scientists. Every scientist has their own barriers to overcome, but let’s beware of extrapolating that, because something was not an issue for us, it is therefore not seriously problematic for those around us.

During the pandemic and its aftermath, relying on conventional thinking and others’ biased experience is more dangerous than ever, especially due to the documented ethnic-, class- and gender-based disparities of COVID-19 in our communities2,3,4.

Those of us who are senior enough to be giving advice and setting expectations can enhance the quality and inclusivity of our working environments by asking our students and colleagues about the barriers they face, with a view to understanding the factors that might exclude people from career progression. Those around you might well have had to deal with hardships and circumstances that are different from yours: so when involved in mentoring conversations, make time to ask which ways forward would work for them, rather than just recommending your own path. The fact that you overcame a barrier does not preclude it unfairly excluding many others.

Seeking further mentorship and support from others whose background is similar to yours, and who have faced similar barriers in their career, can be particularly helpful in this regard. Frank but sensitive conversations around these issues might feel awkward, but in helping us better understand how to support one another, they could be key to reducing inequities in scientific careers.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02634-z

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged.

References

1. Wang, Y., Jones, B. F. & Wang, D. Nature Commun. 10, 4331 (2019).

2. Blundell, R., Dias, M. C., Joyce, R. & Xu, X. Fiscal Stud. 41, 291–319 (2020).

3. Gemelas, J., Davison, J., Keltner, C. & Ing, S. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-00963-3 (2021).

4. Malisch, J. L. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 15378–15381 (2020).

- Karlston

-

1

1

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.