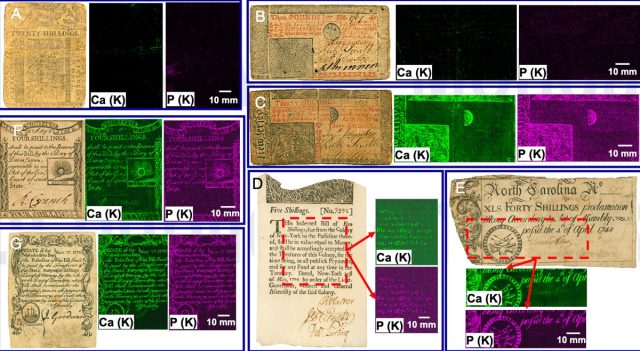

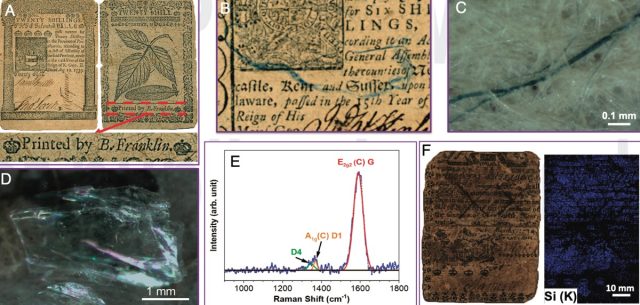

A papermaker in Massachusetts named Zenas Marshall Craneis traditionally credited with being the first to include tiny fibres in the paper pulp used to print currency in 1844. But scientists at the University of Notre Dame have found evidence that Benjamin Franklin was incorporating coloured fibres into his own printed currency much earlier, among other findings, according to a new paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

We first reported on Franklin's ingenious currency innovations—most likely intended to foil counterfeiters (although this is disputedby at least one economist)—in 2021, when Notre Dame nuclear physicist Michael Wiescher gave a talk summarizing his group's early findings. The new paper, co-authored by Weischer, covers those earlier results along with the coloured fibre evidence. As previously reported, the American colonies initially adopted the bartering system of the Native Americans, trading furs and strings of decorative shells known as wampum, as well as crops and imported manufactured items like nails. But the Boston Mint used Spanish silver between 1653 and 1686 for minting coins, adding a little copper or iron to increase their profits (a common practice).

The first paper money appeared in 1690 when the Massachusetts Bay Colony printed paper currency to pay soldiers to fight campaigns against the French in Canada. The other colonies soon followed suit, although there was no uniform system of value for any of the currency. To combat the inevitable counterfeiters, government printers sometimes made indentations in the cut of the bill, which would be matched to government records to redeem the bills for coins. But this method wasn't ideal since paper currency was prone to damage.

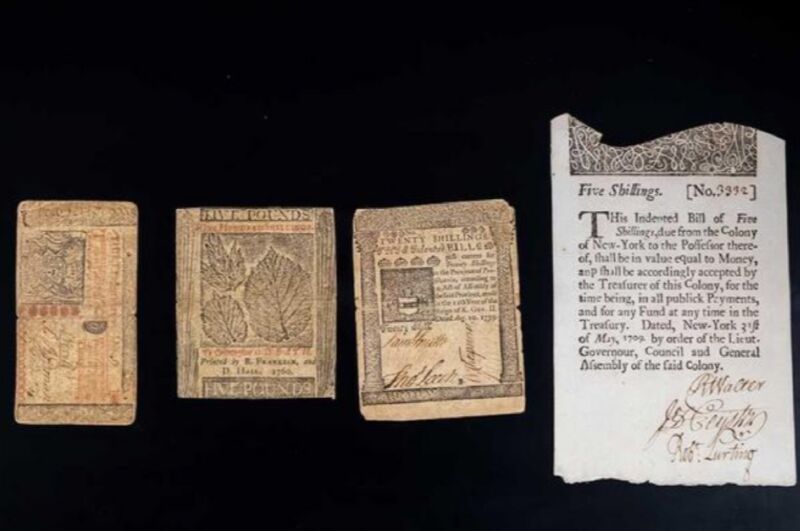

By the time he was 23, Franklin was a successful newspaper editor and printer in Philadelphia, publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette and eventually becoming rich as the pseudonymous author of Poor Richard's Almanack. Franklin was a strong advocate of paper currency from the start. For instance, in 1736, he printed a new currency for New Jersey, a service he also provided for Pennsylvania and Delaware. And he designed the first currency of the Continental Congress in 1775, depicting 13 colonies as linked rings forming a circle, within which "We are one" was inscribed. (The reverse inscription read, "Mind your business," because Franklin had a bit of cheek.)

“Benjamin Franklin saw that the Colonies’ financial independence was necessary for their political independence," said co-author Khachatur Manukyan. "Most of the silver and gold coins brought to the British American colonies were rapidly drained away to pay for manufactured goods imported from abroad, leaving the Colonies without sufficient monetary supply to expand their economy.”

Naturally, counterfeiters didn't take long to introduce fake currency, and Franklin and his network constantly generated new ways to distinguish fake bills. Some forms of those techniques are still used to detect forgeries today. For instance, in 1739, Franklin's printed currency for Pennsylvania deliberately misspelled the state's name. The intent was to set a trap for counterfeiters, who presumably would correct the misspellings in their forgeries.

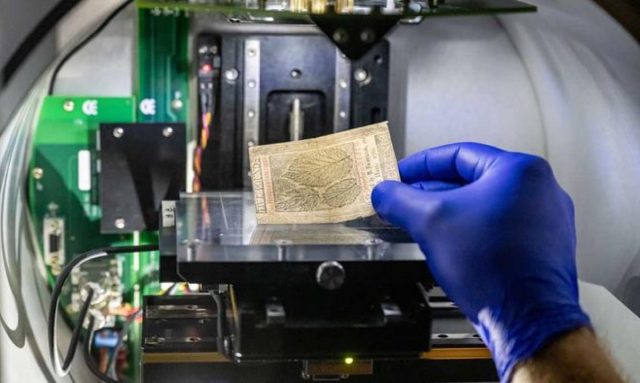

Franklin kept a separate ledger, in addition to his main account book, in which he recorded his dealings with a papermaker named Anthony Newhouse. Franklin purchased "money paper" from Newhouse sometime in the mid- to late 1740s, and likely kept those transactions separate to keep his work on security features confidential, per the authors. “To maintain the notes’ dependability, Franklin had to stay a step ahead of counterfeiters,” said Manukyan. “But the ledger where we know he recorded these printing decisions and methods has been lost to history. Using the techniques of physics, we have been able to restore, in part, some of what that record would have shown.”

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.