If you think black holes are the scariest things in the Universe, I have something to share with you.

There are balls of dead matter no bigger than a city yet shining a hundred times brighter than the Sun that send out flares of X-rays visible across the galaxy. Their interiors are made of superfluid subatomic particles, and they have cores of exotic and unknown states of matter. Their lifetime is only a few thousand years.

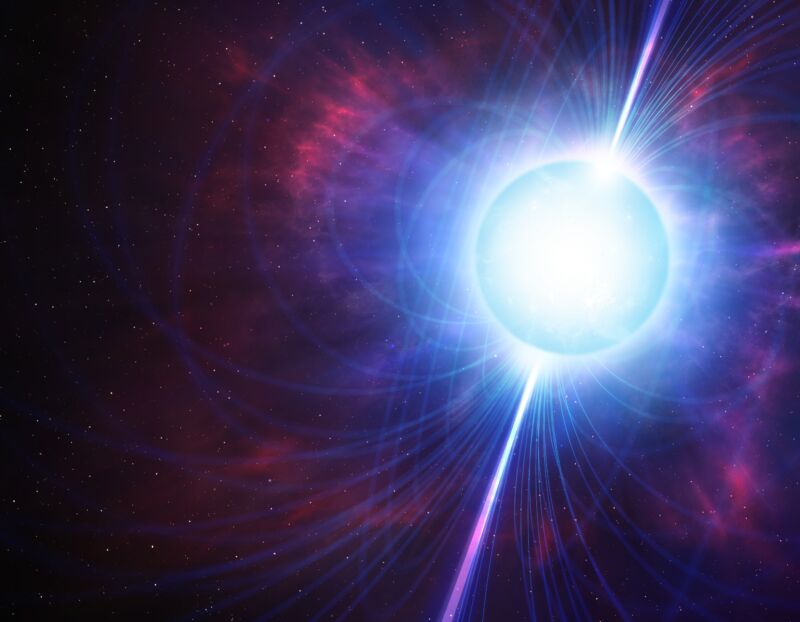

And here's the best part: They have the strongest magnetic fields ever observed, so strong they can melt you—literally dissociate you down to the atomic level—from a thousand kilometers away.

These are the magnetars, perhaps the most fearsome entities ever known.

Little green men

The best discoveries in science happen by accident, and to get to magnetars, we have to trace them through two unexpected observations.

The first came in 1967, when graduate student Jocelyn Bell (now Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell) was working with her advisor, Antony Hewish, on the newly constructed and very fancy Interplanetary Scintillation Array at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory in Cambridge, United Kingdom. While pouring over one night's data, she found "a bit of scruff" (her words). It was a strikingly regular pattern, a flash of radio emission repeating every 1.33 seconds. Further observations showed that the signal came from the same point in the sky night after night, ruling out a terrestrial source.

At first, Bell and Hewish didn't know what to make of it. It was so regular and predictable that they half-jokingly called the source "LGM-1," wondering if "little green men" (i.e., aliens) might be responsible for the mysterious signal.

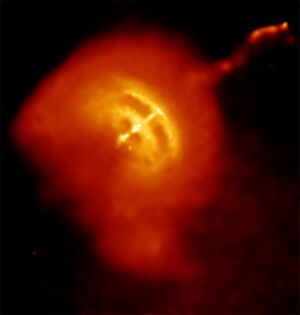

These objects came to be known as pulsars, a situation of pure coincidence. The rotating neutron star can emit beams of radiation that sweep out in circles like a lighthouse. When they flash over the Earth, we see them as a repeating pattern.

(In an unfortunate bit of history, Hewish won the Nobel prize for the discovery, but the committee excluded Bell.)

Around the same time, the United States Department of Defense launched a series of satellites, known as the Vela satellites, to monitor the Soviet Union for any naughtiness—specifically, any signs of violations of the nuclear test ban treaty. If the Soviets tested a nuclear bomb, it would release a flood of gamma rays that the Vela satellites could see from space.

The Vela satellites did indeed see a lot of flashes of gamma rays—but they came from the wrong direction. For years, the satellites monitored flash after flash coming from deep space and cataloged the mysterious events.

In 1973, the satellites finally let the astronomers in on the secret, and gamma-ray astronomy was born. After decades of study, astronomers realized that there were many different kinds of gamma-ray signals, with one in particular, the soft gamma repeaters, doing exactly what the name suggests: repeating.

To generate gamma rays (even the "soft" ones that are still incredibly powerful), you need a lot of energy, especially in the form of electromagnetic fields. And to make those emissions regular, you need something to be rotating. Astrophysicists realized that the best explanation for the origins of these soft gamma ray bursts was that they were beefed-up versions of pulsars, which would mean a highly magnetized neutron star.

In the 1990s, the concept of the magnetar was born.

If you get within approximately 1,000 kilometers of a magnetar, you die. Instantly. Leaving aside the copious amount of X-ray radiation constantly pouring out of these objects (we'll get to that), the magnetic fields make life literally impossible. The problem is that atoms are made of positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons. In weak magnetic fields, this doesn't make a bit of difference. But in strong fields, the electrons and protons respond differently. Atoms lose their traditional shape, and the electron orbitals become elongated along the direction of the magnetic field lines.

If you somehow made it to the surface of a magnetar, your individual atoms would only be 1 percent as wide as they are long. With atoms turning into needles, atomic physics as we know it breaks down. As does all the bonds that atoms use to glue themselves together into complex molecules.

In other words, the static magnetic field of a magnetar is strong enough to simply... dissociate you. All the molecules that you're made of simply come apart into oddly shaped atoms.

These insanely strong magnetic fields also affect the vacuum of space-time and the quantum foam, the seething froth of particles that constantly appear and disappear at subatomic scales. Many of those particles are electrically charged, and at these field strengths, the particles gyrate around the magnetic field lines at nearly the speed of light. This produces something called a birefringence in the vacuum itself. Like ordinary cellophane, the birefringence can split light into separate directions, leading to weird optical illusions, distortions, and magnification—all from the simple presence of the magnetic field.

The heart of a killer

Like all neutron stars, magnetars aren't very large. A typical neutron star will have a diameter of just around 20 kilometers. But within that small volume, they will hold up to twice the mass of the Sun, making them the densest known objects in the cosmos, one step shy of black holes themselves (which aren't objects in any traditional sense). A single teaspoon of neutron star material weighs somewhere around 100 million tons. To support themselves against catastrophic gravitational collapse, neutron stars don't rely on the release of energy from nuclear fusion but rather an exotic quantum phenomenon known as degeneracy pressure.

At densities comparable to that of an atomic nucleus, the neutrons that make up the bulk of these objects aren't able to occupy the same energy states at the same time. This puts a limit on the densities they can reach. Another way to look at degeneracy pressure is to remember Heisenberg's uncertainty principle: You can't ever know both a particle's position and velocity accurately at the same time. By cramming the neutrons in so tightly against each other, you know their positions extremely well. But this causes their velocities to skyrocket, vibrating them like angry trapped bees. This buzzing velocity provides a source of pressure against further collapse.

What happens inside a magnetar is a matter of pure speculation. Physicists think that the surface of a magnetar is covered in a shell of heavy atomic nuclei and free electrons. Because of the intense gravity, these surfaces are incredibly smooth; the highest "mountains" will only be a couple of centimeters tall. But don't think of them as trivial. If you were to fall off one of those mountains, by the time you reached the bottom, you would already be traveling at half the speed of light.

Deeper into the magnetar, the atomic nuclei eventually dissociate in a sea of neutrons. Due to the enormous stresses, the neutrons compress and compact into odd shapes: lumps, tubes, and other tangled knots known affectionately as nuclear pasta. The cores of magnetars are beyond the realm of known physics. It could just be a superfluid of neutrons or other strange states of matter (as in, literally made of a soup of strange quarks).

Fully armed and operational

In normal, everyday neutron stars, the power to generate radiation comes from the initial heat of their formation and the loss of rotational energy as they slow down. With magnetars, the energy contained in the magnetic field completely swamps any other source. If you were to convert its energy density into mass via E/c2, the magnetic field would be 10,000 more dense than lead.

By itself, a magnetar is hot enough to generate enormous amounts of X-ray radiation due to its surface temperature of nearly 20 million Kelvin. But with magnetars, there's more. The magnetic field of a magnetar whips particles around it at a healthy fraction of the speed of light. These high-energy particles then slam into any photons that wander nearby, energizing them through a process called Compton scattering and turning them into more X-rays. The same magnetic fields funnel charged particles directly into the crust like a roided-out version of our own aurorae, generating even more X-rays.

The result is that magnetars are around a hundred times more luminous than the Sun, but they generate all that radiation from a volume roughly the size of Manhattan. Plus, magnetars radiate almost exclusively in X-rays, which is significantly less pleasant than the gentle warmth of our own star.

Sometimes, the extreme magnetic field pins down on the charged particles of the crust with almost overwhelming force. To relieve itself of the enormous pressure, the crust of a magnetar suddenly shifts, rearranging itself to find a new equilibrium that sustains the heavy magnetic load. This process triggers the release of an enormous amount of energy stored in the magnetic field (imagine pressing on one corner of a table until the leg underneath buckles—you're going to lose some energy as you fall to the ground). The extreme energies lost by the magnetic field produce a flood of electrons and positrons, which then recombine to form a storm of gamma rays.

After the release, the magnetar settles back into its normal X-ray-producing mode. But after enough time, the pressures build back up, and the only relief is a new arrangement of the crust, triggering another round of gamma ray emission. This is what causes those soft gamma repeaters discovered by the Department of Defense.

The rearranging of a magnetar's field may also be responsible for yet other mysterious cosmic flashes. Astronomers recently discovered a fast radio burst—a blaze of radio energies that lasts for only a fraction of a second—going off in our own galaxy and found that its origins coincided with a known magnetar. Magnetars may also be responsible for superluminous supernovae, in which a flaring magnetar can reenergize the remnants of the supernova that birthed it, causing both to suddenly and dramatically rise in brightness.

Alas, like all good things, the party must come to an end. The extreme magnetic fields act as a drag, slowing down the spin of the magnetar and providing an avenue for energy to escape. Within about 10,000 years, a magnetar will turn into just another normal neutron star—still exotic but without that sharp magnetic edge.

Astronomers know only about 24 magnetars, almost all of them found within our galaxy. Their short lifetimes mean that we will only ever see a minority of the potential ones in the time that we've been capable of observing them. But given what we know, astronomers estimate that there are around 30 million dead magnetars within the Milky Way galaxy alone.

It was fun while it lasted.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.