Last year, researchers sequenced the genome of famed composer Ludwig van Beethoven for the first time, based on authenticated locks of hair. The same team has now analyzed two of the locks for toxic substances and found extremely high levels of lead, as well as arsenic and mercury, according to a recent letter published in the journal Clinical Chemistry.

“It definitely shows Beethoven was exposed to high concentrations of lead,” Paul Janetto, co-author and director of the Mayo Clinic's Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, told The New York Times. “These are the highest values in hair I’ve ever seen. We get samples from around the world, and these values are an order of magnitude higher.” That said, the authors concluded that the lead exposure was not sufficient to actually kill the composer, although Beethoven very likely did suffer adverse health effects because of it.

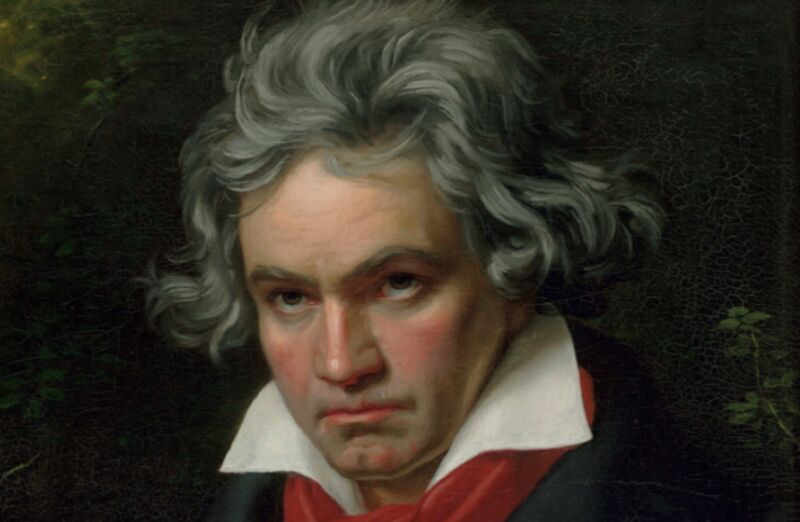

As previously reported, Beethoven was plagued throughout his life by myriad health problems. The composer began losing his hearing in his mid- to late 20s, experiencing tinnitus and the loss of high-tone frequencies in particular. He claimed the onset began with a fit in 1798 induced by a quarrel with a singer. By his mid-40s, he was functionally deaf and unable to perform public concerts, although he could still compose music.

Beethoven on his deathbed: lithograph by Josef Danhauser after his own drawing.

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Beethoven also had lifelong chronic gastric ailments, including persistent abdominal pains and prolonged stretches of diarrhea. By 1821, the composer showed signs of liver disease, marked by the first of two severe attacks of jaundice. These issues certainly affected his career and emotional state, so much so that Beethoven requested—via a letter addressed to his brothers—that his favorite physician examine his body after his death to determine the cause of all his suffering.

By December 1826, Beethoven was quite ill, suffering from a second bout of jaundice and swollen limbs, fever, dropsy, and labored breathing. His doctor performed several operations to remove excess fluid from the composer's abdomen. On March 24, 1827, he purportedly said to visitors, "Plaudite, amici, comoedia finita est" ("Applaud, friends, the comedy is over"). Two days later, he died. According to his good friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner, who was present, lightning and a loud clap of thunder briefly woke Beethoven, who "opened his eyes, lifted his right hand and looked up for several seconds with his fist clenched... not another breath, not a heartbeat more."

An autopsy identified severe liver damage (evidence of cirrhosis) as the likely cause of death and significant dilation of the auditory nerve. But what caused that liver damage or his hearing loss—or his chronic stomach complaints, for that matter? Medical detectives have been debating possible causes for nearly two centuries, drawing on the composer's letters, diaries, and physicians' notes for evidence, as well as reports on skeletal remains from when his body was exhumed in 1863 and 1888. But no general consensus emerged.

Last year, scientists successfully sequenced Beethoven's genome based on samples taken from five authenticated preserved locks of hair. While the analysis of that genome failed to pinpoint a definitive cause of Beethoven's hearing loss or chronic digestive problems, he did have numerous risk factors for liver disease and was infected with hepatitis B. The researchers also found genetic evidence that somewhere in the Beethoven paternal line, an ancestor had an extramarital affair.

Past scholars have attributed the hearing loss to otosclerosis, or possibly lead poisoning from the wines Beethoven preferred. The composer's contemporaries thought his alcohol consumption was moderate, although standards were different in the early 19th century, and his own "conversation books" show he was a regular drinker. He may have been drinking as much as a liter a day around 1825–1826, and there does seem to be a family history of alcohol dependence and liver disease. Plus the wine in Beethoven's time often contained lead sugar (lead acetate), with the corks often being pre-soaked in lead salt to get a better seal. Alternatively, it could have been due to complications from when he contracted murine typhus in 1796.

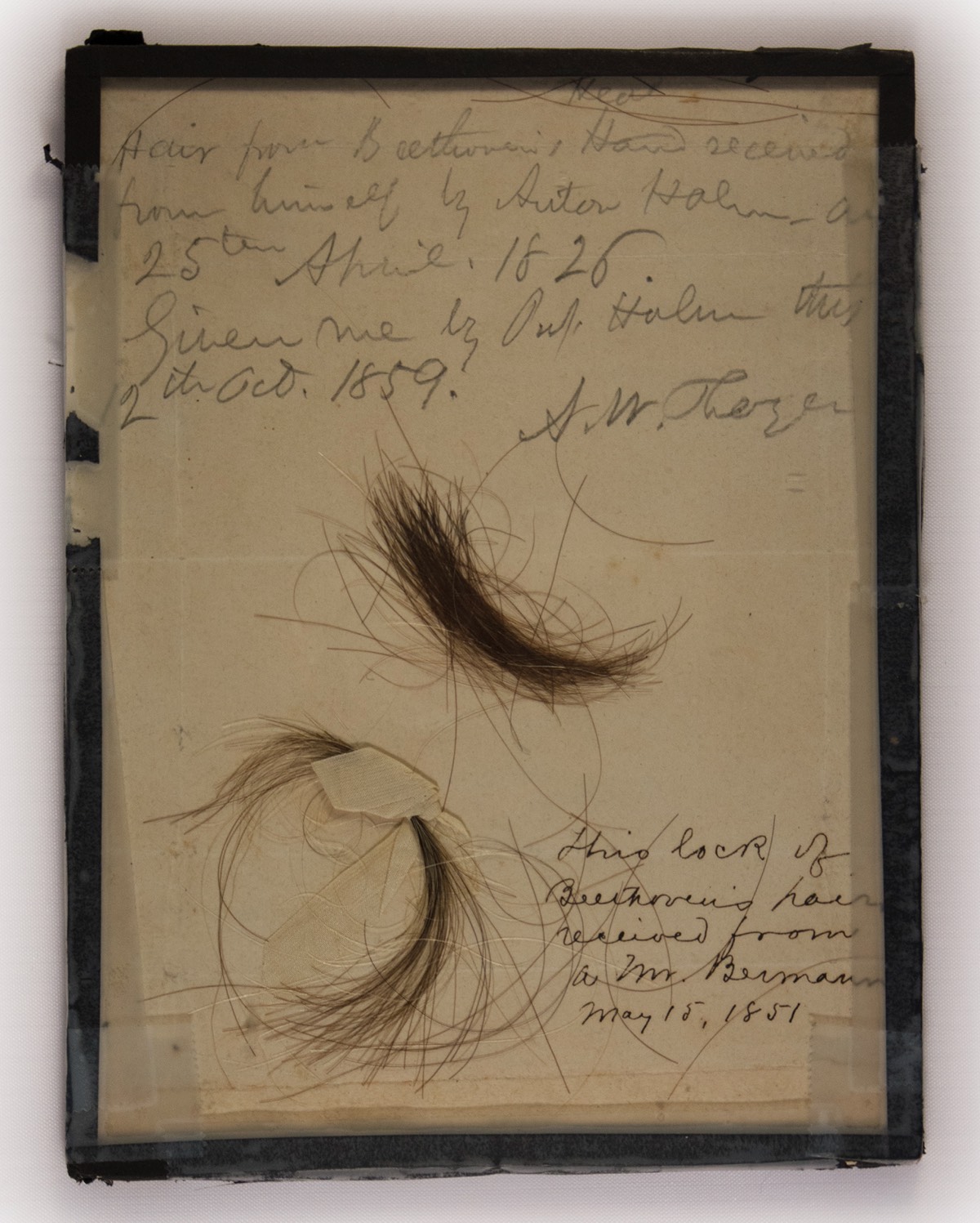

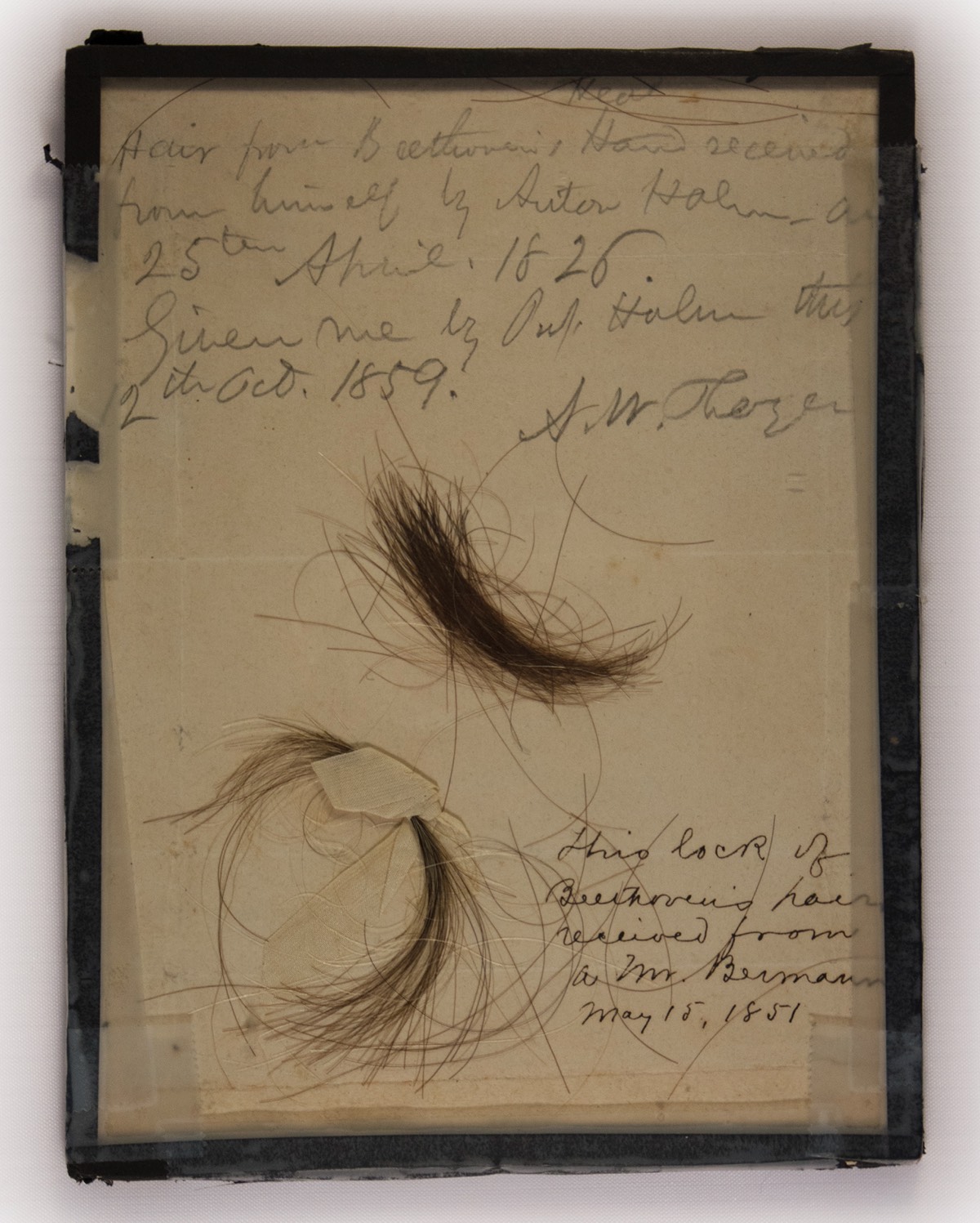

The Halm-Thayer lock and the Bermann lock, both authenticated by the 2023 study.

Kevin Brown

Toxicological analysis of hair samples claimed to be those of Beethoven had been done in the past, along with an examination of skull fragments. But the lead poisoning argument rested largely on a lock of hair (the Hiller lock) that the 2023 analysis showed was not authentic and actually belonged to a woman. So the same team decided to perform toxicological testing on two of the authenticated five locks using mass spectroscopy—the Bermann lock and the Halm-Thayer lock. The Hall-Thayer lock was particularly of interest because it's the only one known to have come from Beethoven himself; the composer hand-delivered it to his friend, pianist Anton Hall, in April 1826.

The team found that the Bermann lock had very high levels of lead—64 times higher than the upper limit of what is considered typical in a healthy person—while the Hall-Thayer lock had lead levels 95 times higher. That means the amount of lead in Beethoven's blood could have been between 69 and 71 micrograms per deciliter. "Such lead levels are commonly associated with gastrointestinal and renal ailments and decreased hearing but are not considered high enough to be the sole cause of death," the authors wrote.

The authors acknowledged certain limitations to their analysis. For instance, hair samples can be contaminated by environmental lead as well as contaminants in artificial hair treatments like dyes. However, there is no evidence that Beethoven ever used such treatments, and the study protocols removed any external contaminants prior to testing. It's also true that high lead levels in hair may not be a good predictor of levels in the blood, although the authors note prior research showing a correlation between high lead hair levels and kidney and liver disease.

"While the concentrations determined are not supportive of the notion that lead exposure caused Beethoven's death, it may have contributed to the documented ailments that plagued him most of his life," the authors concluded. "We believe this is an important piece of a complex puzzle and will enable historians, physicians, and scientists to better understand the medical history of the great composer."

Clinical Chemistry, 2024. DOI: 10.1093/clinchem/hvae054 (About DOIs).

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.