Ars Technica had the opportunity to tour NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California this week, suiting up for a clean room sneak peek at the Psyche spacecraft now nearing completion. This ambitious mission, named after the eponymous asteroid it will explore, is due to launch in August on a Falcon Heavy rocket. Scientists are hopeful that learning more about this unusual asteroid will advance our understanding of planet formation and the earliest days of our solar system.

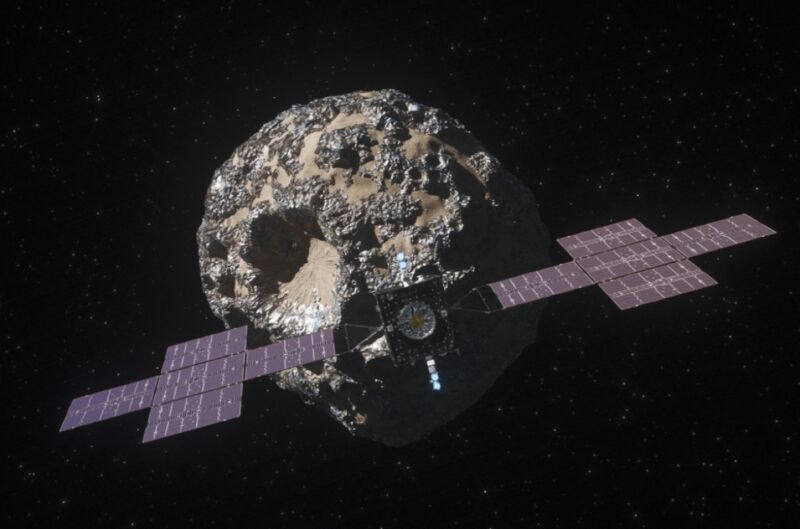

Discovered in March 1852 by the Italian astronomer Annibale de Gasparis, 16 Psyche is an M-type asteroid (meaning it has high metallic content) orbiting the Sun in the main asteroid belt, with an unusual potato-like shape. The longstanding preferred hypothesis is that Psyche is the exposed metallic core of a protoplanet (planetesimal) from the earliest days of our solar system, with the crust and mantle stripped away by a collision (or multiple collisions) with other objects. In recent years, scientists concluded that the mass and density estimates aren't consistent with an entirely metallic remnant core. Rather, it's more likely a complex mix of metals and silicates.

Alternatively, the asteroid might once have been a parent body for a particular class of stony-iron meteorites, one that broke up and re-accreted into a mix of metal and silicate. Or perhaps it's an object like 1 Ceres, a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter—except 16 Psyche may have experienced a period of iron volcanism while cooling, leaving highly enriched metals in those volcanic centers.

Scientists have long suspected that metallic cores lurk deep within terrestrial planets like Earth. But those cores are buried too far beneath rocky mantles and crusts for researchers to find out. As the only metallic core-like body discovered, Psyche provides the perfect opportunity to shed light on how the rocky planets in our solar system (Earth, Mercury, Venus, and Mars) may have formed. NASA approved the Psyche mission in 2017, intending to send a spacecraft to orbit the asteroid and collect crucial data about its characteristics.

"Our understanding of what Psyche might be has not changed all that much over the last few years," Linda Elkins-Tanton of Arizona State University, principal investigator of the Psyche mission, told Ars. "It has to have a large metal content, but we've never really known how much. It could be the part of a metal core of a tiny planet from early in the solar system, or it could be something that never melted and formed a core but has metal mixed into it, like pebbles with the rock. We won't really know until we get there."

Several instruments will be aboard the Psyche spacecraft to collect that precious scientific data. There is a multi-spectral imager capable of producing sufficiently high-resolution images for scientists to tell the difference between the asteroid's metallic and silicate (mineral) constituents. The job of mapping the asteroid's composition and identifying all the elements falls to a gamma ray and neutron spectrometer. There is also a magnetometer that will measure and map any remnants of a magnetic field. Finally, a microwave radio telecommunications system will also be able to measure the asteroid's gravity field, gleaning clues about its interior structure.

The chassis, constructed by a satellite company called Maxar Technologies, was delivered last April. It's roughly the size of a passenger van and was built largely from commercial, off-the-shelf technology. "Once in space, the spacecraft will use an innovative means of propulsion, known as Hall thrusters, to reach the asteroid," Ars Senior Space Editor Eric Berger wrote last year. "This will be the first time a spacecraft has ventured into deep space using Hall thrusters, and absent this technology, the Psyche mission probably wouldn't be happening—certainly not at its cost of just less than $1 billion." Here's a bit more from Berger about this innovative approach:

Engines powered by chemical propulsion are great for getting rockets off the surface of the Earth when you need a brawny burst of energy to break out of the planet's gravitational well. But chemical rocket engines are not the most fuel-efficient machines in the world, as they guzzle propellant. And once a spacecraft is in space, there are more fuel-efficient means of moving around. NASA has been experimenting with [solar electric propulsion] technology for a while. The space agency first tested electric propulsion technology in its Deep Space 1 mission, which launched in 1998, and later in the Dawn mission in 2007 that visited Vesta and Ceres in the asteroid belt.

These spacecraft used ion thrusters. Hall thrusters, by contrast, use a simpler design, with a magnetic field to confine the flow of propellant. These thrusters were invented in the Soviet Union and later adapted for commercial purposes by Maxar and other companies. Many of the largest communications satellites in geostationary orbit today, such as those delivering DirecTV, use Hall thrusters for station-keeping.

Using Hall thruster-based technology enabled the mission's scientists and engineers to design a smaller and more affordable spacecraft. Each of the Hall thrusters on Psyche will generate three times as much thrust as the ion thrusters on the Dawn spacecraft and can process twice as much power. This will allow the spacecraft to reach the Psyche asteroid, located in the main belt, in January 2026, after a 3.5-year journey.

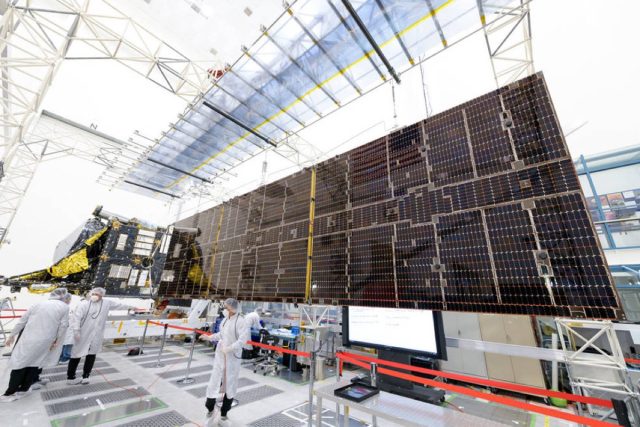

The Psyche team tested the twin solar arrays in March, attaching the arrays to the spacecraft body and unfolding them lengthwise, before stowing the panels until the August launch. The five-panel, cross-shaped solar arrays are the largest installed at JPL, measuring 800 square feet (75 square meters). They are specially designed to work in low-light conditions, far away from the Sun.

After launching from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in August, the Psyche spacecraft will plug along on its Hall thrusters until it reaches Mars in May 2023. Then it will slingshot around the red planet for a gravitational assist for the final leg of the journey to its namesake asteroid.

"The most important thing is to get the engine and thrusters going right away," JPL's Henry Stone, Psyche project manager, told Ars. "This is not a chemical propulsion, this is an electrical propulsion mission. That means we are powering the vehicle, propulsing all the way to Psyche, in addition to doing a gravitational assist around Mars. We need to launch the vehicle, get it into a safe state quickly, and be prepared to get the engines up and running so that we can get to the final destination."

Once everything is up and running, testing will begin on a laser communications experiment called Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC), which will operate for about a year. The objective of this optical system is to improve the performance of spacecraft communications substantially over conventional radio frequency (rf) systems, similar to how fiber optic cables replaced old-school telephone wires.

"There's a huge bandwidth crunch," JPL's Abhijit "Abi" Biswas, DSOC project technologist, told Ars. "We're running out of bandwidth because of demand from near-Earth satellites. Moving to optical opens up a nice slice of spectrum. You get much higher data rates than rf— roughly a factor of 10 for large distances—all for the same mass and power, once we work out all the kinks. We have targeted data rates at targeted distances so if we can hit those data rates, then definitely it's worked."

DSOC boasts a flight laser transceiver, a ground laser transmitter, and a ground laser receiver. The experiment on board the Psyche spacecraft is a proof of principle. Substantial infrastructure on the ground would need to be developed for similar optical systems to be deployed in future missions. "There has to be some investment in that because, for deep space, you need large aperture ground collectors which don't exist today," Biswas said.

For the Psyche technology demonstration, Biswas' team is relying on the near-infrared laser transmitter at JPL's Table Mountain facility, with the Hale Telescope at California's Palomar Observatory serving as a receiver. But that won't be operationally feasible for broad deployment on future deep space missions, such as a manned mission to Mars. According to Biswas, JPL is currently experimenting with putting mirrors on the Goldstone antennas in hopes of using the same infrastructure to operate in both the optical and rf regimes.

The spacecraft will reach the asteroid in January 2026 and spend the next 21 months in orbit mapping the body and measuring its properties. There will be three orbital stages, as the spacecraft gradually dips into successively lower orbits until it is orbiting just 53 miles (85 kilometers) above the surface.

Because the asteroid Psyche has such an odd shape, the mission scientists expect it most likely has a very irregular gravitational field. "We had to design the spacecraft in such a way to be able to account for that from a navigation and control standpoint," said Stone. "That's in part why we start out at a very high altitude, so we can safely orbit far away, and make measurements of the gravitational field. Then we can build that model and refine it in real time, so that we then know how to drop down successively these closer and closer orbits."

And then we wait for all that data to be analyzed so Psyche can reveal its secrets. "My secret hope is that Psyche is not part of a metal core, that it's something quite unusual," Elkins-Tanton said. "I would love for it to be 'reduced': Some material that had all its oxygen stripped off it so that the metal is made up of the iron that's left behind. Some previously undetected building block of planets, something we haven't seen in the meteorite collection. That would be the biggest thrill to me."

"High Bay Bob" is an unofficial mascot of the High Bay clean rooms at JPL.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.