Lacing the beer served at their feasts with hallucinogens may have helped an ancient Peruvian people known as the Wari forge political alliances and expand their empire, according to a new paper published in the journal Antiquity. Recent excavations at a remote Wari outpost called Quilcapampa unearthed seeds from the vilca tree that can be used to produce a potent hallucinogenic drug. The authors think the Wari held one big final blowout before the site was abandoned.

“This is, to my knowledge, the first finding of vilca at a Wari site where we can get a glimpse of its use,” co-author Matthew Biwer, an archaeobotanist at Dickinson College, told Gizmodo. “Vilca seeds or residue has been found in burial tombs before, but we could only assume how it was used. These findings point to a more nuanced understanding of Wari feasting and politics and how vilca was implicated in these practices.”

The Wari empire lasted from around 500 CE to 1100 CE in the central highlands of Peru. There is some debate among scholars as to whether the network of roadways linking various provincial cities constituted a bona fide empire as opposed to a loose economic network. But the Wari's construction of complex, distinctive architecture and the 2013 discovery of an imperial royal tomb lend credence to the Wari's empire status. The culture began to decline around 800 CE, largely due to drought. Many central buildings were blocked up, suggesting people thought they might return if the rains did, and there is archaeological evidence of possible warfare and raiding in the empire's final days as the local infrastructure collapsed and supply chains failed.

Before that, however, the Wari enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity, with a capital city (just northeast of today's city of Ayacucho in Peru) that served as the center of the Wari civilization. The use of hallucinogens, particularly a substance derived from the seeds of the vilca tree, was common in the region during the so-called Middle Horizon period, when the Wari empire thrived.

Vilca typically grows in the dry tropical forests in the region. The trees produce long legumes filled with thin seeds. The seeds, bark, and other parts of the tree all contain DMT, a well-known psychedelic substance that is also found in the ayahuasca brews of Amazonian tribes. However, the primary active ingredient is bufotenine, the effects of which quickly wear off if the drug is taken orally. So it's usually smoked, ingested in the form of snuff, or used as an enema by those seeking the full hallucinogenic effect. A 4,000-year-old pipe laced with bufotenine residue and related paraphernalia was found in an Incan cave in Argentina in 1999—the oldest archaeological evidence to date for using vilca in South America.

There is also evidence from historical accounts that a juice or tea derived from vilca seeds was sometimes added to chicha, a fermented beverage made from maize or the fruits of the molle tree native to Peru. This is one way to take vilca orally while still getting a weaker, sustained psychedelic effect, since the beta-carbolines produced during the fermentation of chicha suppress the stomach enzymes that counter the high by deactivating the active compounds. "Collective consumption of vilca-infused beverages is also documented ethnographically, with the more sustained experiences recounted contrasting with the overwhelming hallucinogenic rush produced when consumed in other manners," the authors wrote.

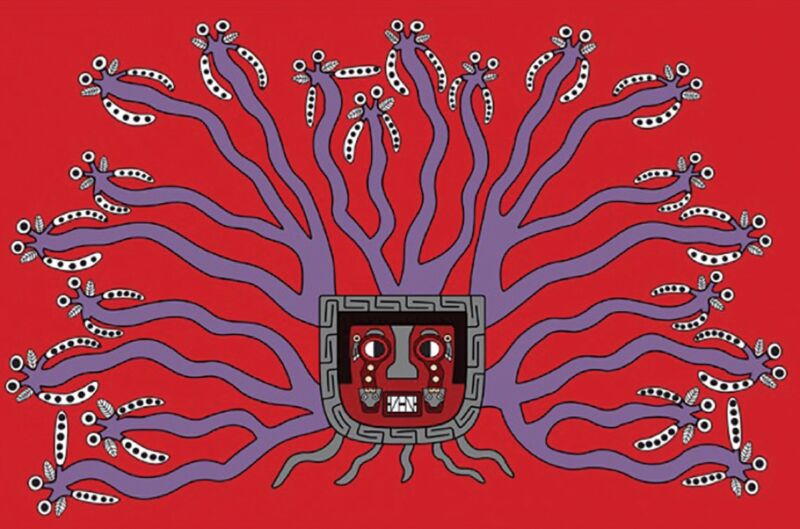

For instance, people of the neighboring state of Tiwanaku were known to mix such hallucinogens with alcohol, specifically maize beer. There are monoliths depicting figures holding a drinking cup in one hand and a snuff tray in another, and smoking or inhaling vilca was part of a long-standing ritual tradition to foster personal spiritual journeys.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.