The 4,000-year-old skull and mandible of an Egyptian man show signs of cancerous lesions and tool marks, according to a recent paper published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine. Those marks could be signs that someone tried to operate on the man shortly before his death or performed the ancient Egyptian equivalent of an autopsy to learn more about the cancer after death.

“This finding is unique evidence of how ancient Egyptian medicine would have tried to deal with or explore cancer more than 4,000 years ago,” said co-author Edgard Camarós, a paleopathologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela. “This is an extraordinary new perspective in our understanding of the history of medicine.”

Archaeologists have found evidence of various examples of primitive surgery dating back several thousand years. For instance, in 2022, archaeologists excavated a 5,300-year-old skull of an elderly woman (about 65 years old) from a Spanish tomb. They determined that seven cut marks near the left ear canal were strong evidence of a primitive surgical procedure to treat a middle ear infection. The team also identified a flint blade that may have been used as a cauterizing tool. By the 17th century, this was a fairly common procedure to treat acute ear infections, and skulls showing evidence of a mastoidectomy have been found in Croatia (11th century), Italy (18th and 19th centuries), and Copenhagen (19th or early 20th century).

Cranial trepanation—the drilling of a hole in the head—is perhaps the oldest known example of skull surgery and one that is still practiced today, albeit rarely. It typically involves drilling or scraping a hole into the skull to expose the dura mater, the outermost of three layers of connective tissue, called meninges, that surround and protect the brain and spinal cord. Accidentally piercing that layer could result in infection or damage to the underlying blood vessels. The practice dates back 7,000 to 10,000 years, as evidenced by cave paintings and human remains. During the Middle Ages, trepanation was performed to treat such ailments as seizures and skull fractures.

Just last year, scientists analyzed the skull of a medieval woman who once lived in central Italy and found evidence that she experienced at least two brain surgeries consistent with the practice of trepanation. Why the woman in question was subjected to such a risky invasive surgical procedure remains speculative, since there were no lesions suggesting the presence of trauma, tumors, congenital diseases, or other pathologies. A few weeks later, another team announced that they had found evidence of trepanation in the remains of a man buried between 1550 and 1450 BCE at the Tel Megiddo archaeological site in Israel. Those remains (of two brothers) showed evidence of developmental anomalies in the bones and indications of extensive lesions—signs of a likely chronic debilitating disease, such as leprosy or Cleidocranial dysplasia.

Ancient Egypt also had quite advanced medical knowledge for treating specific diseases and traumatic injuries like bone trauma, according to Camarós and his co-authors. There is paleopathological evidence of trepanation, prosthetics, and dental fillings, and historical sources describe various therapies and surgeries, including mention of tumors and "eating" lesions indicative of malignancy. They thought that cancer may have been much more prevalent in ancient Egypt than previously assumed, and if so, it seemed likely that Egyptians would have developed methods for therapy or surgery to treat those cancers.

-

Skull E270, dating from between 663 and 343 BCE, belonged to a female individual who was older than 50 years.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

Skull E270, dating from between 663 and 343 BCE, belonged to a female individual who was older than 50 years.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024 -

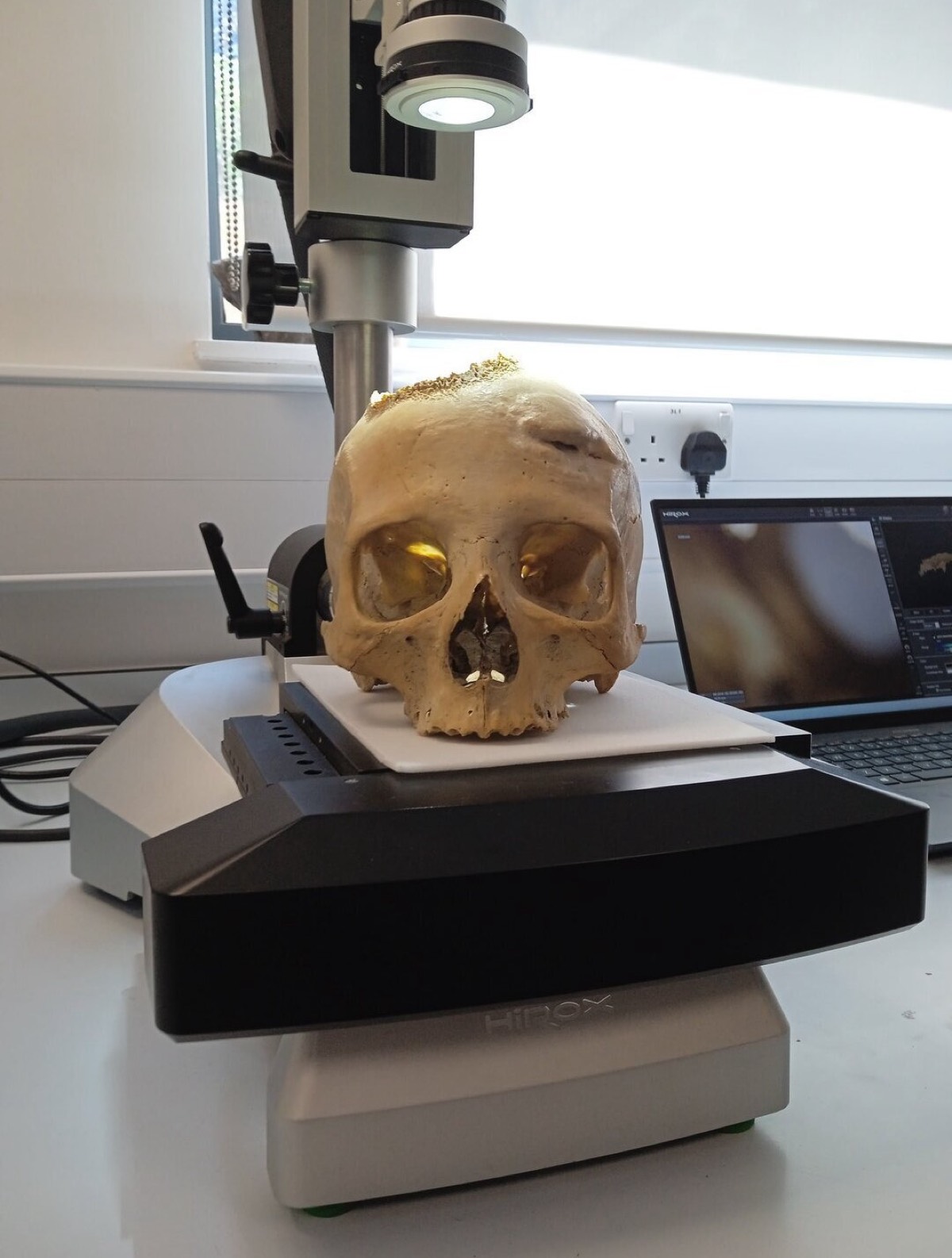

The skulls were examined using microscopic analysis and CT scanning.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

The skulls were examined using microscopic analysis and CT scanning.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024 -

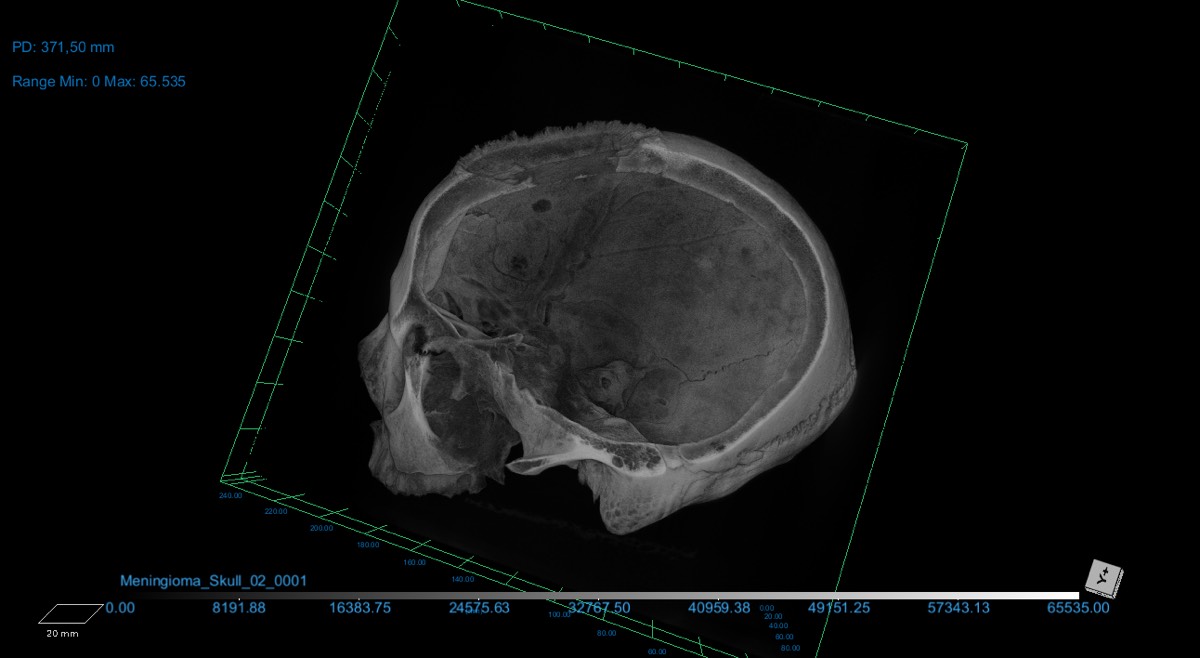

CT Scan of skull.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

CT Scan of skull.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024 -

Cutmarks found on skull 236, probably made with a sharp object.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

Cutmarks found on skull 236, probably made with a sharp object.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024 -

Several of the metastatic lesions on skull 236 display cutmarks.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

Several of the metastatic lesions on skull 236 display cutmarks.Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.