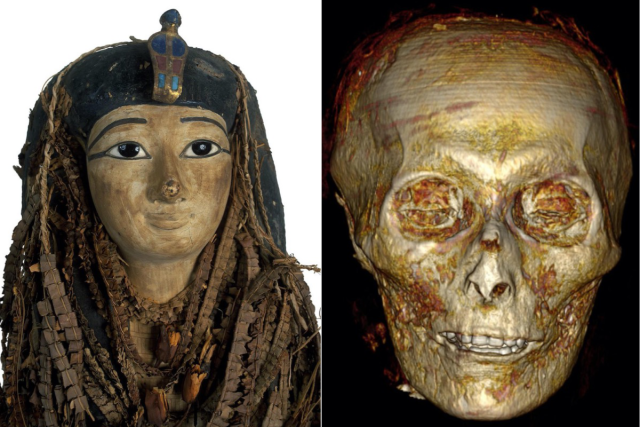

Amenhotep I was an Egyptian pharaoh best known for building numerous temples and inspiring the formation of a funerary cult after his death. His mummy, first discovered in 1881, has never been opened, because conservators were reluctant to damage something that had survived in such pristine condition. Now, scientists have succeeded in "virtually unwrapping" the mummy of Amenhotep I, providing us with our first look inside, according to a paper published last week in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

In the process, the authors disproved their own hypothesis that those who restored the mummy sometime during the 21st dynasty (1069 to 945 BCE) did so in order to reuse the royal burial equipment for later pharaohs. Instead, Amenhotep I's mummy seems to have been lovingly restored after being damaged by tomb robbers.

"This fact that Amenhotep I's mummy had never been unwrapped in modern times gave us a unique opportunity: not just to study how he had originally been mummified and buried, but also how he had been treated and reburied twice, centuries after his death, by High Priests of Amun," said Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, the radiologist of the Egyptian Mummy Project, who co-authored the paper with Zahi Hawass, former minister of antiquities of Egypt. "By digitally unwrapping the mummy and 'peeling off' its virtual layers—the facemask, the bandages, and the mummy itself—we could study this well-preserved pharaoh in unprecedented detail."

This isn't the first such digital unwrapping. As we reported in 2020, an interdisciplinary team of scientists digitally "unwrapped" three mummified animal specimens—a cat, bird, and snake—using a high-resolution 3D X-ray imaging, essentially enabling them to conduct a virtual postmortem. Just last month, another team used an automated "virtual segmentation method" to more accurately visualize mummified Egyptian animals. And in 2019, we reported that German scientists used a combination of cutting-edge physics techniques to virtually "unfold" an ancient Egyptian papyrus. Their analysis revealed that a seemingly blank patch on the papyrus actually contained characters written in what had become "invisible ink" after centuries of exposure to light.

Little is known about Amenhotep I, who was the second ruler of the 18th dynasty. He succeeding his father, Ahmose I, despite having at least two older brothers who should have inherited the throne. Both presumed heirs, however, died before Ahmose I, making Amenhotep crown prince. He assumed the throne in 1526 BCE and was probably young enough at the time that his mother, Ahmose-Nefertiti, likely ruled as regent for a time. He married his older sister, Ahmose-Meritamun, as his Great Royal Wife (although it's also possible she was his grandmother).

During Amenhotep I's reign, the Egyptian Book of the Dead may have been completed in its final form, and there is evidence that the first water clock was invented, too, although the oldest surviving such mechanism dates to the later reign of Amenhotep III. The pharaoh also built a number of temples, including his own mortuary temple and tomb, which he kept separate, presumably to safeguard his remains (and treasures) from looters. He died in 1506 BCE, with no living heirs, and was succeeded by Thutmose I. After his death, he was deified as a god.

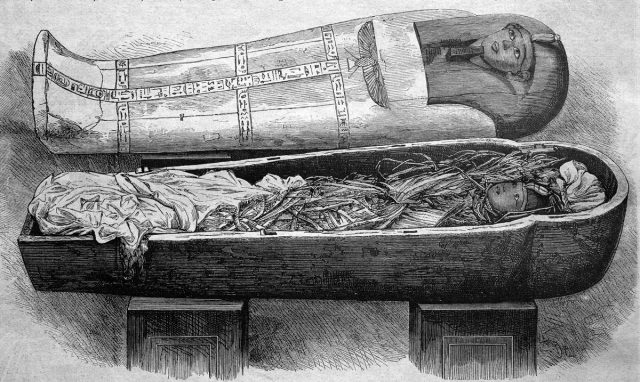

Amenhotep I's mummy was relocated sometime during the 20th or 21st dynasty, perhaps to protect it from looters. The exact location of Amenhotep I's tomb still hasn't been discovered, but his mummy was recovered in 1881 at a site called Deir el-Bahari in Luxor, along with several others. Initially, the mummy was kept at the Boulaq Museum before it was moved to a palace in Giza.

By 1902, all the mummies from Deir el-Bahari were transferred to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The Egyptologist in charge, Gaston Maspero, opted not to unwrap Amenhotep I's mummy because the wrappings were still so perfectly preserved. Apparently, when the coffin was first opened, he found a preserved wasp inside, presumably drawn by the aroma of the garlands.

There have been two prior X-ray studies of Amenhotep I's mummy. The first was done in 1932 by the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and the resulting images were used to conclude that the pharaoh had been around 50 years old at the time of his death. This estimate was contradicted by a second set of X-rays taken in 1967; these pegged the age of death at around 25 years, based on the relatively good condition of the teeth. The 1967 images also revealed a beaded girdle, the right forearm flexed at the elbow and crossing the chest, and a broken left arm resting along the mummy's flank.

According to Saleem and Hawass, the issue with conventional X-rays is that a 3D image is projected onto 2D film. This causes objects and bones to be superimposed, making the results difficult to interpret accurately—including the condition of the teeth. By contrast, CT imaging takes hundreds of thin slices of the body, and software then assembles those slides into more detailed images. This is why it has proven so popular for noninvasively imaging wrapped mummies.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.