As interest in academia fades, scholars in PhD and master’s programmes are dubious about the value of their degree in advancing their professional lives, finds Nature survey.

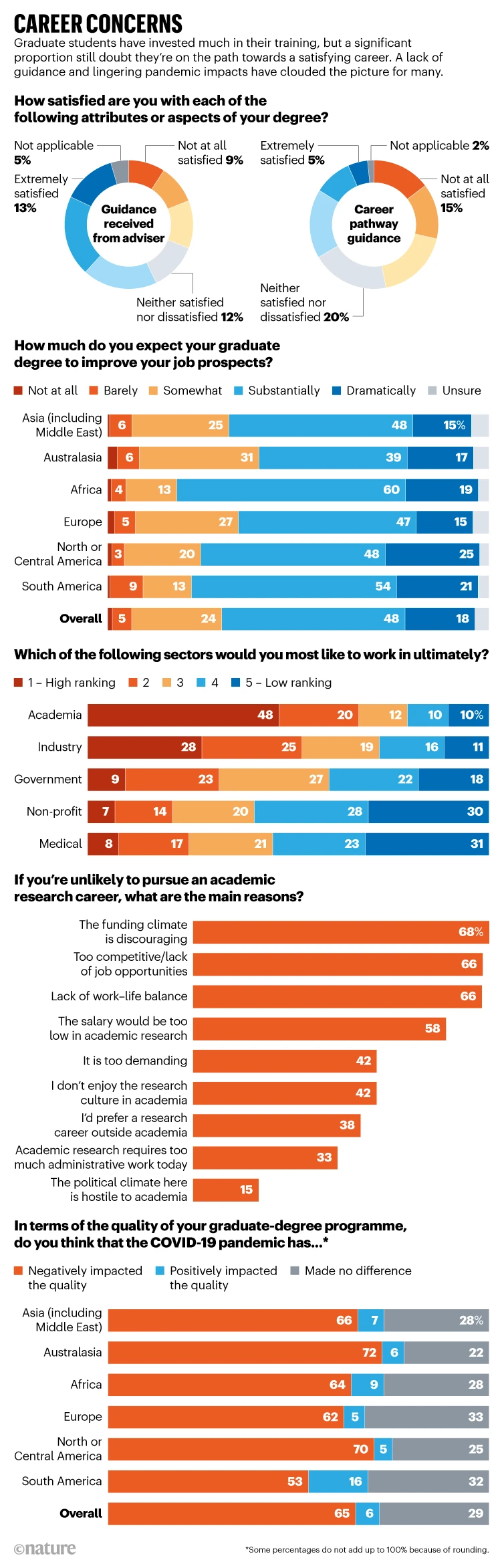

One-third of respondents to Nature’s 2022 global graduate-student survey are lukewarm about the value of their current programme. Sixty-six per cent of the PhD and masters’ students who responded think that their degree will “substantially” or “dramatically” improve their job prospects, but the rest see little or no benefit. Less than one-third agree that they expect to find a permanent job within one year of graduating, or that their programme is leaving them well prepared to eventually find a satisfying career.

“I don’t think a PhD degree will do me much good,” says survey respondent Joshua Caley, a master’s student at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, a country where the impacts of COVID‑19 and economic uncertainty continue to cloud job prospects. Caley plans to pursue a PhD after his master’s, mainly to spend more time studying his topic — the biochemical basis of age-related disease — but he doesn’t have any expectation that an advanced degree will help him to advance his career. “I have a lot of friends and colleagues who did a PhD,” he says, “and it didn’t really help them out”.

More than 3,200 self-selected respondents from around the world took part in the questionnaire (see ‘Nature’s graduate student survey’). It was the journal’s first such survey since the start of the pandemic, and the first to include master’s as well as PhD students. The results point to widespread uncertainty about career paths and the value of advanced degrees (see ‘Career concerns’).

The survey also highlights a significant disconnect between the training that students are receiving and the realities of their future careers, says Shweta Ganapati, a policy adviser at the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada in Ottawa. “There has been a shift in the labour market, and PhD programmes have not changed sufficiently to adapt,” says Ganapati, who reviewed the results. “There’s a reason why they are not optimistic. We can fix this, but we aren’t moving fast enough.”

Nearly half (47%) of respondents say that they are dissatisfied with their level of career-pathway guidance and advice, and another 20% are neutral. As a fourth-year PhD student at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, Erika Murce says that she is learning plenty about a career as a university researcher — writing papers, applying for grants, navigating departmental politics. “Most of my training is for academia,” she says. But there’s one big problem: Murce doesn’t want to stay in academia. “I started to see that my supervisor is constantly under pressure,” she says. “I thought, ‘I don’t think I want this kind of life.’”

‘I don’t think I want this kind of life’: Erika Murce plans to quit academia after her PhD because of the constant pressures involved.

Credit: Erika Murce Silva

Murce says that the university is gradually exposing students to other career possibilities. She says that she’ll occasionally receive a newsletter about career options or hear about a career-development seminar at a nearby institution. “In my first year, I barely saw anything like that,” she says. “Maybe there’s a shift in mentality.”

Widespread dissatisfaction with career training was also evident in a questionnaire-based study from 2021, co-authored by Ganapati and Tessy Ritchie, a chemist at the United States Military Academy at West Point in New York. That study gathered responses from 176 PhD students and recent alumni, mostly in the United States, to take a closer look at career development in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Alumni said that they were largely unaware of career options while they were in graduate school, and had few opportunities to prepare for jobs outside academia. (Ganapati and Ritchie point out that they speak for themselves, not for their institutions.)

Shifting aspirations

At a time when career training for graduate students in science remains focused mainly on university-based positions, interest in that sector seems to be fading. Less than half (48%) of respondents say that they would prefer, ultimately, to work in academia. That’s down from 56% in 2019, when Nature last surveyed PhD students. Twenty-eight per cent of respondents in 2022 say that they would most like to work in industry. Other preferred destinations include government (9%), the medical sector (8%) and non-profit institutions (7%).

Ganapati notes that about half of the alumni in her study found academic jobs, but that those included postdoctoral positions and other temporary jobs. “It’s a reality that a very small percentage of PhD graduates will end up with a tenure-track professorship,” she says. In the larger picture, she says, it’s not surprising that enthusiasm for academic careers seems to be on the decline. “Right now, the pay is bad, the work–life balance is bad and mental health is an issue,” she says. “If any of those shift, research jobs in academia will be more appealing.”

Nature’s graduate student survey

This article is the third of six linked to Nature’s global survey of graduate students. Further articles are scheduled for the weeks to follow, including explorations of master’s students’ responses; mobility issues for all participants; and students’ experience of racism and discrimination. The survey was created together with Shift Learning, a market-research company in London, and was advertised on nature.com, in Springer Nature digital products and through e-mail campaigns. It was offered in English, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, French and Portuguese. The full survey data sets are available at go.nature.com/3dyefwg.

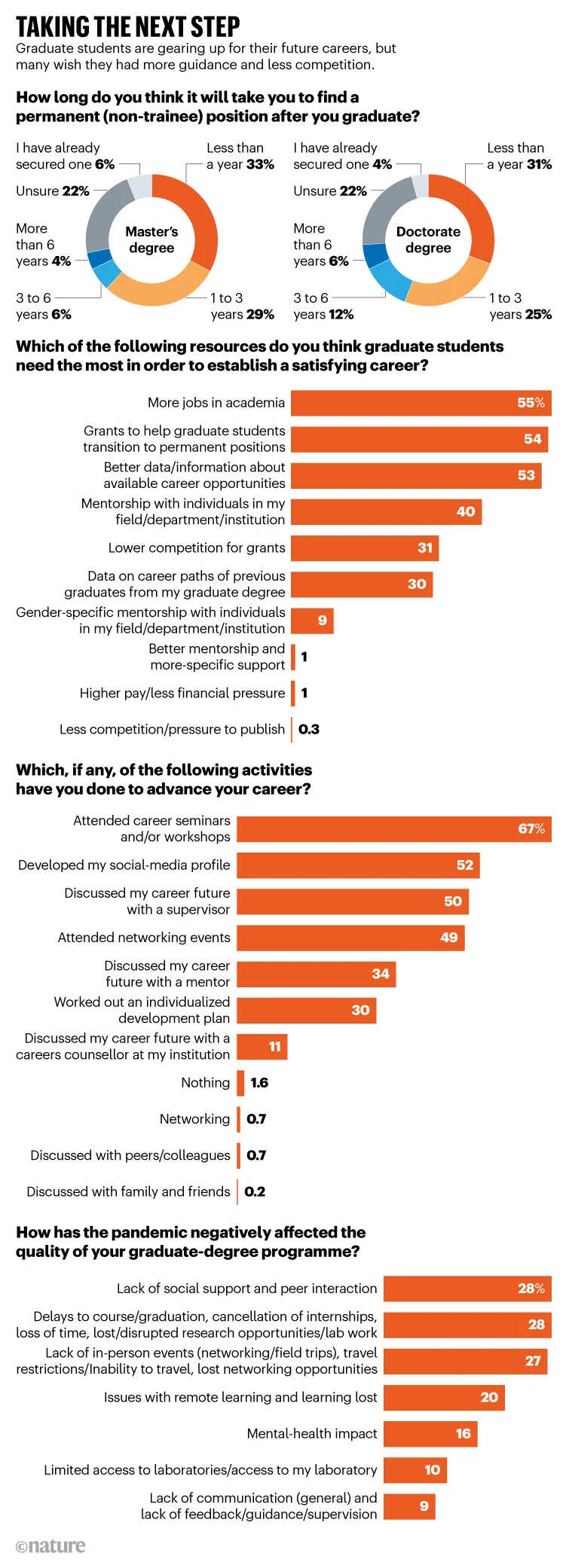

Whatever the ultimate goal, not all graduate students are confident that their degree will help them to get there (see ‘Taking the next step’). Twenty-four per cent of respondents think that their degree will “somewhat” improve their job prospects, and 6% feel that their degree will either “barely” advance their cause or not help at all. Another 4% say that they are unsure how it will affect their career trajectory. When asked to name the biggest difficulties for graduate students in their country, 56% of respondents rank “finding a permanent job after completing my education” among the top three.

“I’m part of a generation of people who were always told by their parents or advisers that a college degree opens doors,” says survey respondent Donna McCullough, a PhD student at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. “But by the time we got to the work field, that was no longer the case.”

‘Political and highly subjective’

Colleen Limegrover, a PhD student in neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, UK, was putting the finishing touches to her degree when she responded to the survey in June 2022. She says that she learnt much about her field during her time at Cambridge, but that pandemic-related shutdowns slowed her progress and made it difficult to publish papers. “You start with rose-coloured glasses about what your programme is going to be like, and it’s hardly ever that way,” she says.

Limegrover, who worked for seven years at a biotechnology start-up in the United States before starting her PhD programme, says she originally thought that her combination of industry experience and PhD training would make it easy to find a management position at a biotech firm. But, she says, her preliminary job searches were discouraging. She found that some companies now expect candidates to have completed a postdoctoral position, and that her years of work at the bench carried surprisingly little weight.

Donna McCulloch is concerned that a PhD no longer ‘opens doors’ to a secure career.

Credit: D. K. McCullough

“How they interpret lines on a résumé is political and highly subjective,” she says. “This archaic mindset that somehow academic experience is more valuable than industry experience needs to change.” (At the time of going to press, Limegrover had just accepted an offer of an industry job in Boston, Massachusetts.)

Other respondents used the survey’s comment section (see ‘Career conversation’) to share misgivings about their training and their futures. “It is not appropriate to do a PhD in clinical-research groups like the one I am in,” wrote a doctoral student in Spain. (The comment was translated from Spanish.) “It is not the priority of supervisors who have other more important tasks as clinicians. In these cases, the student is not properly supervised and there is no correct training.”

Career conversation

Respondents used free-text comments to share their thoughts on training and future careers. Comments have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

I honestly do not know if I’ll end up working in science after my PhD. There are no guarantees. Many of my friends are tutoring high-school science. One even worked in a funeral home for a while. She had a PhD in molecular biology and several years of industry experience. So what hope do I have? — PhD student, South Africa

I thought I wanted to be a professor at a liberal-arts college, but the job market is bad for that and the pay is mostly horrendous. My goal now is to take almost any option that gets me away from the bench. — PhD student, United States

In the UK, a PhD is of little value with regard to a career. There are very few jobs in academia and these are increasingly unattractive in terms of pay and conditions. In industry or other careers, a PhD is unnecessary and would be better avoided. — PhD student, United Kingdom

All of my peers seem to be shocked at the lack of job prospects after they graduate. No one is telling them to look early and network. That’s what I did and now my life is much less stressful. — PhD student, New Zealand

I wish I’d known about the job opportunities available to me with a bachelor’s degree in hospital labs and public-health labs. I now feel like I’m simultaneously overqualified and underqualified. — PhD student, United States

As part of the last year of the master’s degree, my main concern has been finding a PhD to continue my studies. This search has had a deep impact on my mental health throughout the last months. My advice is to start looking for PhD positions as soon as possible. — Master’s student, Italy

A doctoral student in the United States opined: “The academic-research training pipeline is in trouble, but those in the positions to help haven’t realized it yet. Project scientists are leaving. Postdocs are more difficult to recruit, because more leave academia immediately after their PhD now. Who is going to be left to work in these labs? When the PhD is not seen as valuable, then it’s over — but I hope it doesn’t get to that point.”

The Nature survey suggests that lab leaders are an uncertain resource for career advice outside academia. Just over half (51%) of respondents agree that their supervisor makes time for frank discussions about careers, but only 32% say that their supervisor has useful advice for careers outside academia. Students are looking elsewhere for guidance. Fifty-eight per cent say that they have used social networks such as Twitter or LinkedIn to learn about career opportunities, and 43% say that they’ve leaned on their peers for information.

Seventy-seven per cent of respondents feel that their graduate programme is preparing them well for a possible research career. But 32% say that they are less likely to pursue such a career than when they started their programme. Ritchie suspects that the pressures of university research could put some talented people off the entire research enterprise. Students, she says, might well wonder whether they “have what it takes to compete at this level”, she says.

Marketable skills

Most graduate students feel that they are gaining at least some potentially marketable skills, especially ones that would come in handy in an academic career. Eighty-two per cent agree that they are well prepared to collect and analyse data, 76% say that they are learning to conduct experiments, and 72% that they are gaining experience in writing papers for publication in peer-reviewed journals. But relatively few say that they are being taught the necessary skills to manage people (32%), control a large budget (14%) or develop a business plan (12%).

Career training in STEM could greatly improve if universities paid more attention to the preferences and aspirations of graduate students, Ritchie says. For example, many students would like the opportunity to do a company internship as part of their training, but few get that chance.

“Incorporating feedback of students and alumni into improving the services that the university offers is going to set the stage for modernizing the PhD programme as it exists right now,” she says. Universities should develop a culture in which first-year graduate students are already thinking about their professional options and getting the chance to explore them. “If career awareness starts earlier, everybody can go through the process with the training and support that they need.”

Much of the pessimism around careers could be alleviated if students were more aware of their value and of the wide range of potential opportunities, Ganapati says. “Their prospects are good because PhD students can contribute so much to society,” she says. “We all live in knowledge economies. People who can think critically have much to offer.”

Nature 611, 413-416 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03586-8

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.