The World Intellectual Property Organization's Advisory Committee on Enforcement recently heard how DNS providers have the ability to fight online piracy but could also face liability as secondary infringers. Veiled warnings like these are nothing new, but with piracy colossus Fmovies cited as a primary example, pressure on DNS entities is building once again.

Given the extreme financial power and political leverage held by the world’s largest entertainment companies, most obstacles can be pushed aside or simply rolled over. But exceptions do exist.

In the fight against piracy, not only do the smallest gains require an unusual effort but they’re increasingly dependent on the cooperation of third parties, usually those in the online tech sector. If these companies can’t be convinced to commit business resources to the piracy war voluntarily, lawsuits and mandatory conscription can lie ahead.

The message – that internet companies must tackle piracy or be held responsible for taking part in it – is nothing new. Internet service providers, websites, search engines, hosting providers, domain companies, social media services, and advertising companies are all considered part of the problem.

From terminating allegedly infringing users and implementing copyright filters, to due diligence, website blocking, and running a search engine, tech companies can find themselves being held responsible when third parties upset the business models of other third parties. This new commercial reality isn’t just spreading, it has global aspirations.

Control The Phone Book, Control Communications

A presentation prepared for the recent Fifteenth Session of the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Advisory Committee on Enforcement begins with a brief explainer of the Domain Name System (DNS) and how it works. The fundamental importance of DNS to the internet is glaringly obvious.

So that humans don’t have to remember thousands of IP addresses to access their favorite websites, the DNS system holds all of those numbers in a database and matches them to more easily remembered domain names. When domain names are entered into a browser (Google.com, for example), DNS converts the domain into an IP address and the page appears. If done properly, it’s completely invisible.

At the time of writing, a couple of billion websites rely on the ability of the DNS system to carry out these conversions. The problem for rightsholders is that some of those sites facilitate access to their copyrighted works, and with easy-to-remember names such as thepiratebay.org, they are too easy for people to find.

Following legal action, ISPs in dozens of countries are now required to prevent their customers from accessing sites like thepiratebay.org. Since ISPs carry their own copy of the DNS ‘phone book’, they look up thepiratebay.org, find the IP address allocated to it, and exchange it for a completely useless one.

Rightsholders like this arrangement. Critics say that internet infrastructure shouldn’t tell lies to its users.

So Why Such Drastic Action? FMovies….and a Few Others

If The Pirate Bay’s resistance to shutdown helped to fuel the early days of pirate site blocking, sites like FMovies may end up shouldering the blame for more extreme measures.

With close to 87 million visits per month via desktop alone, FMovies is not only massive but quite possibly the most comprehensive pirate VOD-style streaming site available today. It operates many domains in various jurisdictions under multiple brandings, and isn’t confined to the mainstream movie and TV show ‘niches’ either.

Hollywood companies have forced ISPs in several countries to tamper with the site’s local DNS entries after obtaining injunctions or voluntary cooperation. The site’s traffic continues to grow because it’s still online – DNS tampering cannot change that, not for FMovies or any other site

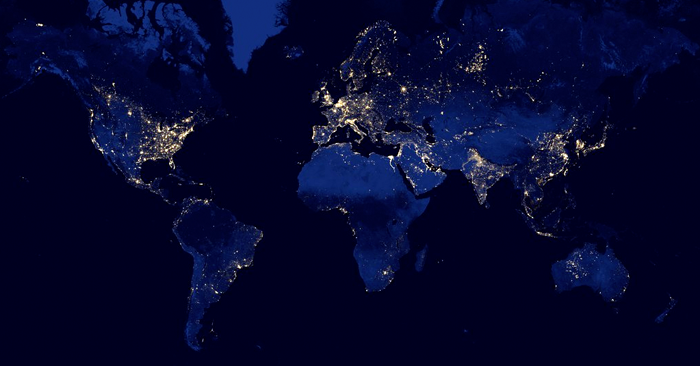

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the presentation is that it talks about options for action against DNS, yet reveals the countries where FMovies has infrastructure, names the companies allegedly supporting that infrastructure, and puts their locations on a map.

So what action could be taken by DNS service providers to take FMovies offline, render it inaccessible, or even make it marginally less successful than it currently is? The presentation has some ideas but before we come to them, it might be worth looking at the slide again.

Why would meddling with the DNS system, which has zero ability to remove content, be preferred over actually removing content?

OVH and M247, two companies listed as serving FMovies, are very large hosting operations and couldn’t hide even if they wanted to. The fact that they are in the EU renders them legally ‘accessible’ too, in the event that they are indeed playing host to one of the world’s largest stashes of premium infringing content. They probably have no idea that’s the case, of course, and being cash-rich their lawyers would be very happy to explain that, in court if necessary.

But the real problem here isn’t who has the ability to fight back, it’s that DNS interference has always been portrayed as a tool of last resort, something to be used when everything else fails. The presentation to the WIPO Enforcement Committee even states that DNS resolvers are completely incapable of removing infringing content.

“The legal frameworks and case law lack a clear picture at international and national levels. Case law mainly discusses liability as secondary infringers if DNS providers serve structurally copyright infringing websites. This usually requires intent, which could be established by a notice,” it reads.

Sony Music certainly hopes that will be enough.

Quad9 DNS Resolver Dispute

In Germany, Swiss-based DNS resolver Quad9 is now in direct legal conflict with Sony Music after refusing to cooperate in the label’s campaign to have a music piracy site blocked. Sony took the case to court, arguing that Quad9 has a duty of care to block the site – a site that doesn’t carry infringing content itself but links to content hosted on another site (or sites), somewhere else entirely.

Perhaps with an eye on the type of intent mentioned above, Sony did indeed give Quad9 clear notice of the infringement. Unfortunately for Quad9, Germany sets the bar for involvement very low indeed, which makes it the perfect venue for this kind of lawsuit.

Under the legal concept of Störerhaftung, otherwise known as disturbance or disruptor liability, a disruptor is someone who is involved in any way with the distribution of illicit content. As involvement goes, Quad9’s role is either extremely minimal or absolutely crucial, depending on perspective.

Sony currently appears to have the upper hand (1,2) and although it’s not over yet(1), some liability protection has already been stripped away. According to a German regional court, since Quad9 only triggers IP address queries to DNS servers and transmits no information, it does not qualify for ‘mere conduit’ liability exemptions.

Cloudflare Ordered to Block Pirate Sites

If Quad9 loses, any order compelling it to block will be part of the package waved around in other jurisdictions to achieve the same goals: do providers want to cooperate now, or perhaps they prefer legal conscription? In the EU, this type of approach has a tendency to spread, where one ruling leads to another and then becomes the accepted norm as intermediaries concede defeat.

And momentum is building.

In July, an Italian court ordered Cloudflare to block three torrent sites on its public DNS resolver 1.1.1.1. Music industry group FIMI said that since the Cloudflare service helps people to access pirate sites, Cloudflare becomes part of the piracy problem. The court agreed and issued a preliminary injunction against Cloudflare.

While copyright holders have shown their intent in no uncertain terms, Cloudflare is drawing its own lines in the sand. While it has been compelled to block in both Italy and in Germany, Cloudflare recently said it will fight any ‘global’ blocking requests if they target its 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver.

Less Aggressive Options

If DNS entities get tired of the lawsuits, it’s possible they could be tempted by so-called non-fault injunctions, the presentation suggests. Popular in the UK and India, the idea is that intermediaries are named as respondents in blocking applications but copyright holders have no intention to sue them.

Everyone involved acknowledges that the intermediaries are in a good position to help out and that everyone’s rights should be respected under the principle of proportionality. This balances copyright holders’ rights, the intermediaries’ rights, and the rights of internet users to access information. The important thing is that there is no conflict and as long as applicants follow procedure, blocking tends to get the court’s seal of approval.

Another favored option doesn’t involve the courts at all because direct agreements between copyright holders and intermediaries do all of the heavy lifting. By designating groups such as the MPA as ‘Trusted Notifiers’, DNS entities could follow the lead of two domain registries and decide what should be blocked in private.

“Proactive measures by DNS providers to discourage online infringement and other illegal activity should be adopted, such as ensuring accuracy of registrant/WHOIS data. Voluntary reactive measures, such as trusted notifier arrangements, should be encouraged,” the presentation concludes (pdf).

WIPO says that the views in the presentation on DNS providers and resolvers are those of the authors and are not necessarily shared by WIPO members. The authors are leading Germany copyright attorney Jan Bernd Nordemann and Dean S. Marks, former Deputy General Counsel and Chief of Global Content Protection at the MPA.

Image Credit: Jimmy Nilsson Masth (Unsplash License)

DNS Providers as Piracy Fighters? Enforcement Groups Weigh Options

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.